When you reach a certain age the Korean Government start to write to you inviting you into a hospital of your choice for an annual medical, which helpfully serves as a reminder that you might have more years behind you than ahead. Generally, it seems like a good thing, because in England people are encouraged to get sick or die before visiting a medical professional; the public health service long since discovered that the longer it can avoid treating sick people, the greater the chance of them expiring before expensive drugs and care need to be employed. In Korea, the Government seems to want to prevent you getting seriously ill in the first place, and I'm sure the private health insurance industry here is grateful for that.

The trip to the hospital got off to a worrying start after discovering an ambulance parked at the entrance bearing the legend “Pusan Mental Hospital”. Just the day before, I'd read about a new law that allegedly enabled the Government to detain foreigners without trial on mental health grounds, in an article which ended with the words of a Korean wife saying "Now I can trick my non-Korean speaking husband into attending the hospital on some pretext, explain some of his habits to the doctors, and get rid of him." Worrying.

Given that the article is a satire, or at least I hope it is because the original news story leaves some room for doubt, I took this as proof that my life may now finally be approaching the point of maximum absurdity it's possible to reach as a private citizen without becoming a government employee. Five minutes later we were filling in the psyche questionnaire.

How many times a week do I get depressed? How many times a week am I sad? Why does the answer scale only go up to four? “Looks like you might be going to see a psychiatrist” quips my wife as she ticks several numerically high boxes. Thanks. Helpful. I don't know, isn't this normal for a foreigner living in Korea? Well, maybe it isn't, but I have no reference point. But I didn't get referred to a psychiatrist, so maybe it is. Or maybe they don't care, I certainly don't – that's the advantage of feeling down that all those happy people don't want to talk about.

So do I want to have a camera stuck down my throat? No... why would I? Honestly, I know network television in South Korea is so apparently awful that even the North Koreans find it stereotypical these days, but what lengths will medical staff go to just to entertain themselves in front of a TV? The procedure requires me to be heavily sedated or unconscious anyway, and I weigh up the obvious advantages of this versus the inherent risks and decide against it. I'll do it when I actually think I have a problem I thought, slipping into exactly the kind of sociological conditioning the British National Health Service works so hard to cultivate. “Yes,” says the nurse detecting my internal dialogue, “I can see that while you're physically ready for it, you're not mentally ready for it”. I don't even know what that means. What does that mean?

Now comes the really hard sell. So my blood is going be tested for thirteen different problems. Would I like to pay extra and be tested for seventy problems instead? It's only 30,000 won extra. This is how it begins. You can even pay extra to receive a forecast for future medical problems based on a range of additional tests, questionnaires and the hospital computer's random number generator. Or you can visit a fortune teller, because it might be cheaper. Buy into enough extra tests and the one problem they are guaranteed to detect is that you are haemorrhaging money. But I paid for the extra blood tests, because I'm intrigued to know the answer to test number 67 – 'percentage of banana concentrate in blood'.

An x-ray to top-up my Korean half-life, an ultrasound to see if I'm still generally sound, an ECG to test my short-circuits, and we're done. As we walk up the stairs from the dungeon of devices, I reflect on the fact that I'm clearly in much better shape than the hospital building, which is six months old and features an alarmingly large crack running down its side.

When we leave they forget to ask us to pay, resulting in two nurses chasing after us outside the building. Perhaps their unwillingness to wait a few days for my return appointment may not bode well for the test results after all.

Sunday, December 19, 2010

Wednesday, December 01, 2010

Poultrygeist: Night of the Chicken Dead

Having a baby in Korea can expose you to a great deal of culturally odd experiences. There are rules about staying in hospital, rules about keeping the rooms there at high temperatures, beliefs that new mothers shouldn't shower for a week, and when the fortune tellers get involved, the minefield of baby naming to navigate. Eventually, those first few weeks pass by and you're left with your newborn at home, and you think things might start to get a little less strange.

But when my wife came into our office and said "I need a picture of a chicken to hang upside down over the baby's bed", I was hardly even surprised even if I had no idea what the reasoning behind it was. Does there come a point where you've been in Korea so long that nothing surprises you any more?

In this case, it seems there an old belief which has its roots in the practices of Korean Shamanism, and the upshot of it is that if your baby is a bit of a handful, doesn't sleep at night - or at all - and generally cries a lot, you should hang a picture of a chicken (or technically I believe, a rooster), upside down over the baby's bed as this will - apparently - be a calming influence. The reasoning is that during pregnancy the baby generally sleeps during the day and is active at night, so the rooster picture is supposed to reverse the cycle, although it's important that the red part of the rooster's head (the 'comb' - really) is exaggerated, hence the reason why my wife extended it with a red colouring pencil.

Now, it occurs to me that several hundred years ago there wasn't an Internet to download chicken images from, and even having the kind of tools and paper around enabling a person to draw a fair representation of a chicken might have been rare, so I can't help wondering if this means that people back then used to hang real chickens - presumably dead ones - upside down over their babies beds. But I'm afraid to ask. When you can walk into your kitchen and find a pig's head staring at you unannounced from the kitchen table - and I have - anything is possible.

By the way, before you rush out to procure your own chicken, drawn or otherwise, I have to tell you that it doesn't work.

But when my wife came into our office and said "I need a picture of a chicken to hang upside down over the baby's bed", I was hardly even surprised even if I had no idea what the reasoning behind it was. Does there come a point where you've been in Korea so long that nothing surprises you any more?

In this case, it seems there an old belief which has its roots in the practices of Korean Shamanism, and the upshot of it is that if your baby is a bit of a handful, doesn't sleep at night - or at all - and generally cries a lot, you should hang a picture of a chicken (or technically I believe, a rooster), upside down over the baby's bed as this will - apparently - be a calming influence. The reasoning is that during pregnancy the baby generally sleeps during the day and is active at night, so the rooster picture is supposed to reverse the cycle, although it's important that the red part of the rooster's head (the 'comb' - really) is exaggerated, hence the reason why my wife extended it with a red colouring pencil.

Now, it occurs to me that several hundred years ago there wasn't an Internet to download chicken images from, and even having the kind of tools and paper around enabling a person to draw a fair representation of a chicken might have been rare, so I can't help wondering if this means that people back then used to hang real chickens - presumably dead ones - upside down over their babies beds. But I'm afraid to ask. When you can walk into your kitchen and find a pig's head staring at you unannounced from the kitchen table - and I have - anything is possible.

By the way, before you rush out to procure your own chicken, drawn or otherwise, I have to tell you that it doesn't work.

Tags:

babies,

culture,

culture shock,

religion,

strange

Location:

Busan, South Korea

Monday, November 29, 2010

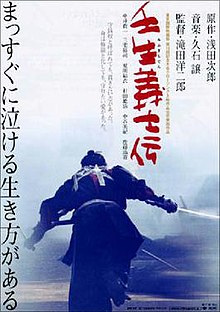

When the Last Sword Is Drawn

You can be free. You can live and work anywhere in the world. You can be independent from routine and not answer to anybody. This is the life of a successful trader. - Alexander Elder - Trading for a Living

You can be free. You can live and work anywhere in the world. You can be independent from routine and not answer to anybody. This is the life of a successful trader. - Alexander Elder - Trading for a LivingI don't write about my job very much; it's usually not relevant to my Korean experiences I document here. Occasionally though, the two worlds do become intertwined.

I've worked for myself as a derivatives trader for the last six years. An oft-repeated statistic is that 90% of financial traders lose money, which makes me one of of the remaining 10%. By that measure you might say I'm good at what I do, but the hours are long, and I'm not so good that I've made enough to retire. Traders often have to work hard to perfect their art, but there comes a time when you have to accept that you might be doing well enough by a lot of people's standards, but 70-hour weeks are not conducive to having much of a life outside work, and for me, those extra hours cut into time that could - and increasingly should - be studying Korean.

So three months ago I finally decided to try and make a transition into something called automated trading – where instead of actually trading I'll code my trading rules into a program called a 'bot' (from 'robot'), and then it will trade for me. Then I free up around 8 hours of my typical 11-hour work day to do other things – such as studying. At least, that's the theory.

Trading is about choosing your weapons as much as it is about yourself - and trading with 'bots' requires a different sword - specialised tools such as MetaTrader and specialised accounts, so you can only do this if companies in America and Europe will do business with people in Korea and the problem is that a lot won't.

For example, one of the world's largest retail forex brokers who I suppose I shouldn't name – it's FXCM – refuses point blank to do business with anyone living in South Korea. Others notionally allow it but make opening an account from here so tortuous that you know they really aren't keen on the idea. Fortunately one of FXCM's large rivals - Alpari - has no such policy and a relatively streamlined (though still far from straightforward) account opening process [edit: see my footnote]. But while this good news, potentially it gives me only one sword to choose from rather than many, and it may not be the sharpest blade. So while it's all very well for Mr. Elder to think you can be free and work anywhere in the world as a trader, clearly he didn't have to put up with trying to be a trader in the modern world outside the US, and certainly not in Korea.

The Korea location problem doesn't just effect trading - try ordering some vitamins from outside Korea and see what an odyssey that can turn into (that blog entry will turn up eventually). And beyond the worlds of trading and vitamin supplements – two areas which I can tell you from personal experience are inextricably linked - lies the pedestrian world of longer-term investments. Just before I moved to Korea I transferred a large portion of my investment holdings from one broker who wouldn't let me be a customer in Korea to HSBC, that said that I could, and two months later HSBC wrote to me in Korea to tell me that after all, they couldn't hold my investments while I lived in Korea – leaving me scrambling to find a broker to move back to – the situation was so dire for a while I thought I might have to completely liquidate my portfolio which would have caused all kinds of tax complications.

Statistically it's unlikely that my foray into the world of automated trading will be successful, but the potential reward justifies the risk and that's what trading is all about. So right now I'm trying to open trading accounts with specialised foreign exchange – or 'forex'/FX – brokers, and because I'm living in Korea I'm hitting the same identity problems here that I have before - I needed my passport and a bank statement stamped and witnessed. The passport may not be a huge problem but my prospective forex broker has no use for a bank statement in Korean – of course it has to be in English with my Korean address on it, which is more of a challenge.

It seems inevitable that I will continue to work at the tenuous sufferance of brokers who treat their support of international customers as a seasonal activity. But to be fair I'm sure the Korean Government don't make it easy for them, because for all their lofty notions of being an 'Asian Financial Hub', the psychological scars from the Asian Financial Crisis mean that they aren't terribly keen on the idea of the free flow of capital, which is a bit of a problem given that - whether you like it or not - it's quite an important aspect of modern global capitalism, especially if you want to be some kind of global financial centre.

So it's true to say, that one way or another, Korea constantly gets in the way of me doing my job. Every day I go out there and do battle on the global financial markets with some of the brightest and dumbest minds this Earth has ever created. Which one am I? Victor or victim? I control my own destiny, financially I live by the sword and die by the sword that are the tools that I use and the way that I wield them. In Korea, that's a fight which I undertake with one arm tied behind my back and the only sword they'll give me. That's the life of a financial trader here.

[edit: I take what I said about Alpari back. After I'd gone through all the document verifications I finally reached the point where I was ready to fund my account. And that's when I found out this wasn't possible electronically because I was in Korea, even though my credit card and bank were in the UK. Alpari hadn't mentioned this small but really quite crucial fact during my emails and phone conversations about opening an account while residing in South Korea, and this would have been bad enough in itself, had they not managed to notch up a first in my many years of trading with many other companies - one of their staff sent me an impolitely worded email. Why it is that Alpari staff think they can vent their frustrations on the company's customers this way is unclear, but I don't have to take that sort of behaviour, and that was the end of my plans with them].

Tags:

business,

customer service,

financial

Location:

Busan, South Korea

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

It's More Expensive to Do Nothing

I'm not writing this to offer any insightful analysis about the attack on South Korea today, this is just an account of how I spent my afternoon and evening.

When my wife came into our office and said something terrible had happened while scrambling to put the news on the TV, a heavy sense of deja vu was already descending on me as she explained that Yeonpyeong Island was being shelled by the North Koreans. It wasn't a surprise; it's long been a potential target and was thought to be under threat recently due to the transition of power in North Korea and in the run-up to the G-20 meeting.

So it was the Cheonan all over again, except this time the attack was immediately more photogenic, and because of the proximity to North Korea's previous attack the thought briefly entered my head that this time, yes - maybe this time - the politicians in Seoul would respond militarily, and hit back against their attackers. Our attackers in fact, because I live here too.

If the North Korean sinking of the Cheonan taught me one thing, it's that you can't rely on the media or the military here to give you accurate information at times like these. And it isn't about media restrictions or secrecy - but rather it's speculation - sometimes wild speculation - dressed up as authoritative fact, seemingly for its own sake. And the media slips into it's Wag the Dog rolling file footage of ships firing their guns and soldiers running around purposefully. You can almost believe you're watching the war live, if a war was really going on.

This time we were told that South Korea had responded militarily, but later this was said to be with the firing of a singular 'K-9 155mm self-propelled howitzer', and the official announcing this declined to say whether North Korean territory had been hit. Which left me rather suspecting that they'd deliberately missed for fear of escalating the situation. Indeed, while the attack was apparently still under-way, President Lee Myung-bak was - truly or falsely - said to be desperately trying to calm the situation.

In the midst of such gravity, the situation tips into apparent farce. The South Korean government have responded to the ongoing attack... with a telegram. And before long the MBC network reported - with a deadly straight face - a South Korean military source complaining "Even though we sent a telegram, they are still firing." Meanwhile we watch South Korean houses burn on TV.

So if you were hoping the still active North Korean artillery positions were going to be targeted, this is the point at which your heart sinks - because you know the script from here on. The South Korean government vow 'stern retaliation' for any further provocations, but South Korea is like a man in a pub who is knocked to the floor by a bully, and gets up waving his finger saying, 'next time you hit me, I'm really going to get mad'. Punch - 'next time' - punch - 'next time' - punch... and so on. The depressing cycle of a country without any idea of what to do about a neighbour that sinks its ships and shells its civilians. Well, not that I do either.

There will be bluster and harsh words spoken by the government in Seoul but just like post-Cheonan they will never amount to much, and the North Koreans will spend tonight laughing at the weakness of their victims. Then they'll blame South Korea for starting it or claim it was an accident. And some in South Korea will even believe them. It's incredibly frustrating to watch, and even more frustrating to live here watching it all unfold.

South Korea is playing a long game, heads-in-the-sand hoping for a North Korean collapse to take the problem away from them. The old-Korea hands brush it off and say they've seen it all before but I believe they're wrong; this is no longer a conventional stand-off, but a nuclear one where only one side has the bombs. South Korea nestles under the U.S. nuclear shield, but if the day comes when North Korean nuclear missiles can reach American cities, or Tea-Party isolationists control Washington, how far can South Korea really rely on its old ally?

The Government in Seoul will try to brush this under the carpet and move on in the name of diplomacy or absurdity. But for tonight at least, the mood in Korea is sombre - and it's enforced - they've cancelled all the light entertainment shows.

And then there's me, and the butterfly effect from North Korea's attack today. I think radio programmes are like sausages. You might like them, but you never want to know how they are made. So you don't want to know how much work I put into preparing for a 10-minute slot I do on Busan e-FM every Wednesday. An hour ago I took a call telling me that tomorrow's topic - which was about festivals - was now predictably inappropriate, leaving me to prepare something entirely new at quite short notice. And it musn't be funny, which makes the task that much harder. So I'll probably talk about Korean apartments, because in my experience, they aren't something to laugh about. But it pains me to go on the air aiming to deliver a bland performance about a subject I will have to make as humourless as possible while not tackling the elephant in the room of what it's like for me to live as a foreigner in Korea at times like these. But I suppose we don't want to depress the listeners either.

It's nobody's fault that these media upheavals happen at times like these (well, apart from North Korea), and my problems are trivial in the scheme of things. Two men are dead, many more people are injured, people have lost their homes, and we can add them to the list of all the other victims of North Korea's unprovoked attacks. We can pretend their deaths will one day be avenged, but they won't. We'll agonise over our collective ineffectiveness for a few days and move on.

When my wife came into our office and said something terrible had happened while scrambling to put the news on the TV, a heavy sense of deja vu was already descending on me as she explained that Yeonpyeong Island was being shelled by the North Koreans. It wasn't a surprise; it's long been a potential target and was thought to be under threat recently due to the transition of power in North Korea and in the run-up to the G-20 meeting.

So it was the Cheonan all over again, except this time the attack was immediately more photogenic, and because of the proximity to North Korea's previous attack the thought briefly entered my head that this time, yes - maybe this time - the politicians in Seoul would respond militarily, and hit back against their attackers. Our attackers in fact, because I live here too.

If the North Korean sinking of the Cheonan taught me one thing, it's that you can't rely on the media or the military here to give you accurate information at times like these. And it isn't about media restrictions or secrecy - but rather it's speculation - sometimes wild speculation - dressed up as authoritative fact, seemingly for its own sake. And the media slips into it's Wag the Dog rolling file footage of ships firing their guns and soldiers running around purposefully. You can almost believe you're watching the war live, if a war was really going on.

This time we were told that South Korea had responded militarily, but later this was said to be with the firing of a singular 'K-9 155mm self-propelled howitzer', and the official announcing this declined to say whether North Korean territory had been hit. Which left me rather suspecting that they'd deliberately missed for fear of escalating the situation. Indeed, while the attack was apparently still under-way, President Lee Myung-bak was - truly or falsely - said to be desperately trying to calm the situation.

In the midst of such gravity, the situation tips into apparent farce. The South Korean government have responded to the ongoing attack... with a telegram. And before long the MBC network reported - with a deadly straight face - a South Korean military source complaining "Even though we sent a telegram, they are still firing." Meanwhile we watch South Korean houses burn on TV.

So if you were hoping the still active North Korean artillery positions were going to be targeted, this is the point at which your heart sinks - because you know the script from here on. The South Korean government vow 'stern retaliation' for any further provocations, but South Korea is like a man in a pub who is knocked to the floor by a bully, and gets up waving his finger saying, 'next time you hit me, I'm really going to get mad'. Punch - 'next time' - punch - 'next time' - punch... and so on. The depressing cycle of a country without any idea of what to do about a neighbour that sinks its ships and shells its civilians. Well, not that I do either.

There will be bluster and harsh words spoken by the government in Seoul but just like post-Cheonan they will never amount to much, and the North Koreans will spend tonight laughing at the weakness of their victims. Then they'll blame South Korea for starting it or claim it was an accident. And some in South Korea will even believe them. It's incredibly frustrating to watch, and even more frustrating to live here watching it all unfold.

South Korea is playing a long game, heads-in-the-sand hoping for a North Korean collapse to take the problem away from them. The old-Korea hands brush it off and say they've seen it all before but I believe they're wrong; this is no longer a conventional stand-off, but a nuclear one where only one side has the bombs. South Korea nestles under the U.S. nuclear shield, but if the day comes when North Korean nuclear missiles can reach American cities, or Tea-Party isolationists control Washington, how far can South Korea really rely on its old ally?

The Government in Seoul will try to brush this under the carpet and move on in the name of diplomacy or absurdity. But for tonight at least, the mood in Korea is sombre - and it's enforced - they've cancelled all the light entertainment shows.

And then there's me, and the butterfly effect from North Korea's attack today. I think radio programmes are like sausages. You might like them, but you never want to know how they are made. So you don't want to know how much work I put into preparing for a 10-minute slot I do on Busan e-FM every Wednesday. An hour ago I took a call telling me that tomorrow's topic - which was about festivals - was now predictably inappropriate, leaving me to prepare something entirely new at quite short notice. And it musn't be funny, which makes the task that much harder. So I'll probably talk about Korean apartments, because in my experience, they aren't something to laugh about. But it pains me to go on the air aiming to deliver a bland performance about a subject I will have to make as humourless as possible while not tackling the elephant in the room of what it's like for me to live as a foreigner in Korea at times like these. But I suppose we don't want to depress the listeners either.

It's nobody's fault that these media upheavals happen at times like these (well, apart from North Korea), and my problems are trivial in the scheme of things. Two men are dead, many more people are injured, people have lost their homes, and we can add them to the list of all the other victims of North Korea's unprovoked attacks. We can pretend their deaths will one day be avenged, but they won't. We'll agonise over our collective ineffectiveness for a few days and move on.

Multiplicity

A few weeks ago I ran into problems registering my son's name with the local district office, and I said it wasn't likely to be the last time having a multicultural child was going to cause problems in Korea. Well I didn't have to wait long for the next issue to raise its head – our son's health insurance bills have arrived and because his Irish surname takes up four Korean character spaces (it's four Western syllables), there was only one character space for his first name rather than two – so he's lost the last syllable of his name. I should have seen this coming because – with my middle name - only the first syllable of my surname appears on my health registration – and this is how I get called out in the hospitals.

This can't be good because when it comes to dealing with officialdom in any country – and I know Korea isn't different – it's quite important to maintain a consistent identity across systems otherwise computers and bureaucrats start to insist that you are not the same person. And when computers start thinking you are different people, the complications can just multiply. Since my son is more Korean than I am – and he'll have to grow up here - I see how it could be a particularly irritating problem for him.

My wife was not confident of our ability to get them to add the extra syllable to his first name, and neither was I because I kind of knew deep down – speaking as an ex-software designer myself - that some incompetent Korean software designer (I'm beginning to wonder if there is really any other kind) decided there was going to be a five-character limit in the database. Because, you know, Koreans don't have such long names and who else would ever be registered in the Korean health system except people with Korean names? Right? (For more on the Korean IT mentality - read this).

I found my wife's initial reaction very telling - “I feel bad now about giving him a strange name”. And that is the wrong answer. Your first reaction is supposed to be righteous indignation, otherwise you've fallen into their trap.

Korea keeps saying it welcomes a multicultural society so I think it would be better if they started planning for it rather than mysteriously thinking that Korea's future multicultural society will consist of people from lots of different countries all pretending they are Korean. Or does Korea really think all the foreigners are going to change their surnames to Kim? Don't answer that – they probably do.

This can't be good because when it comes to dealing with officialdom in any country – and I know Korea isn't different – it's quite important to maintain a consistent identity across systems otherwise computers and bureaucrats start to insist that you are not the same person. And when computers start thinking you are different people, the complications can just multiply. Since my son is more Korean than I am – and he'll have to grow up here - I see how it could be a particularly irritating problem for him.

My wife was not confident of our ability to get them to add the extra syllable to his first name, and neither was I because I kind of knew deep down – speaking as an ex-software designer myself - that some incompetent Korean software designer (I'm beginning to wonder if there is really any other kind) decided there was going to be a five-character limit in the database. Because, you know, Koreans don't have such long names and who else would ever be registered in the Korean health system except people with Korean names? Right? (For more on the Korean IT mentality - read this).

I found my wife's initial reaction very telling - “I feel bad now about giving him a strange name”. And that is the wrong answer. Your first reaction is supposed to be righteous indignation, otherwise you've fallen into their trap.

Korea keeps saying it welcomes a multicultural society so I think it would be better if they started planning for it rather than mysteriously thinking that Korea's future multicultural society will consist of people from lots of different countries all pretending they are Korean. Or does Korea really think all the foreigners are going to change their surnames to Kim? Don't answer that – they probably do.

Tags:

babies,

family,

foreigners,

government,

health

Location:

Busan, South Korea

Friday, November 12, 2010

The Voice in the Wall

Apparently today was 'no car day'. We heard it in an announcement yesterday evening over the Orwellian-style speaker that can't be turned off which is fixed into our apartment wall.

I don't really understand much of what's said by Big Brother, or at least his local representative - the security guards/janitors who skulk in an office in the basement of the building. But sometimes the rambling and slurred delivery leaves little doubt to how some ajeoshis get through their working day. And as jobs go, I'd rather people like this be working as security guards than bus or taxi drivers, although from the quality of the driving of the aforementioned types of vehicles, I'm rather afraid they actually do both.

It's also not clear who designated today 'no car day'. Of course, you'd like to think it was the local council, but then if I worked as a apartment building security guard I imagine I might have great fun making false announcements. Sunglasses day, no bike day, bike day, wear red day and 5am day would all be my ideas. After all, there's only so much pleasure to be had watching people on security cameras, telling them off for incorrect recycling bin allocations, and reminding them every ten minutes that there's a package waiting to be collected from their office until they come to get it. There's a package waiting for you. I still have your package. You should come and collect your package. Package. Package. Package.

I gather that a growing number of Koreans are seeking help from psychiatrists to relieve stress.

Package. Waiting. For You.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there was no discernible lessening of the traffic volume on the road outside this morning. And if, disappointingly, this is some kind of Busan-wide political campaign rather than just being the security guard's late evening solution to boredom, I have to wonder what exactly the politicians expect compliant citizens to do? Is everyone who foregoes the use of their car just expected to pile into the rush hour's (or in Busan, should that be rush hours?) already tightly-packed buses and subway carriages?

Recently I became radio active and started travelling to Busan e-FM every week during the busy commuting period, and they certainly don't call it the '지옥철' - jiogcheol - for nothing (a Korean play on words, 'jihacheol' - 지하철 - means subway, jiog - 지옥 - means hell). Trains come every five minutes and you can't really fault the Busan 'Humetro' Authority, but there are just two many people living here all trying to get to the same places at the same times. No wonder people drive in Busan despite the high risk of death involved.

Oh, did I mention there's a package waiting for you in the janitor's office? Right now. Please.

I don't really understand much of what's said by Big Brother, or at least his local representative - the security guards/janitors who skulk in an office in the basement of the building. But sometimes the rambling and slurred delivery leaves little doubt to how some ajeoshis get through their working day. And as jobs go, I'd rather people like this be working as security guards than bus or taxi drivers, although from the quality of the driving of the aforementioned types of vehicles, I'm rather afraid they actually do both.

It's also not clear who designated today 'no car day'. Of course, you'd like to think it was the local council, but then if I worked as a apartment building security guard I imagine I might have great fun making false announcements. Sunglasses day, no bike day, bike day, wear red day and 5am day would all be my ideas. After all, there's only so much pleasure to be had watching people on security cameras, telling them off for incorrect recycling bin allocations, and reminding them every ten minutes that there's a package waiting to be collected from their office until they come to get it. There's a package waiting for you. I still have your package. You should come and collect your package. Package. Package. Package.

I gather that a growing number of Koreans are seeking help from psychiatrists to relieve stress.

Package. Waiting. For You.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there was no discernible lessening of the traffic volume on the road outside this morning. And if, disappointingly, this is some kind of Busan-wide political campaign rather than just being the security guard's late evening solution to boredom, I have to wonder what exactly the politicians expect compliant citizens to do? Is everyone who foregoes the use of their car just expected to pile into the rush hour's (or in Busan, should that be rush hours?) already tightly-packed buses and subway carriages?

Recently I became radio active and started travelling to Busan e-FM every week during the busy commuting period, and they certainly don't call it the '지옥철' - jiogcheol - for nothing (a Korean play on words, 'jihacheol' - 지하철 - means subway, jiog - 지옥 - means hell). Trains come every five minutes and you can't really fault the Busan 'Humetro' Authority, but there are just two many people living here all trying to get to the same places at the same times. No wonder people drive in Busan despite the high risk of death involved.

Oh, did I mention there's a package waiting for you in the janitor's office? Right now. Please.

Tags:

apartment,

government,

transport

Location:

Busan, South Korea

Thursday, November 11, 2010

The Battle of Tsushima

Korean Mother went on a two day trip to the Japanese island of Tsushima – which is called Daemado in Korea. You shouldn't read too much into the different naming – it doesn't necessarily make it another Dokdo/Takeshima/Liancourt Rocks situation.

However... in March 2005 the local council in Korean city of Masan designated June 19 as Daemado Day, claiming that this was the date in 1419 the island was annexed by the Korean Joseon Dynasty. Therefore, Daemado is Korean territory. But this isn't necessarily just some Tea Party-style fringe movement; in 2008 50 members of the Korean parliament stated their support for the territorial claim over Tsushima, and an opinion poll at the time showed 50.6% support amongst Koreans for the claim. Read on for a little more plot thickening.

So Korean Mother went to Tsushima – or Daemado - and it was meant as a short holiday, not the advanced recon party for a future invasion. Apparently Korean trips to Tsushima are quite popular. I once read that back in the 1980s the best slogan the Korean tourist authorities could come up with for a Japanese campaign was the rather weak but technically correct “Korea – the closest country to Japan” - which is practically apologetic in its lacking of ideas regarding what was attractive about Korea at the time. Now the roles are reversed, because – to paraphrase - Tsushima is the closest part of Japan to Korea.

Unfortunately Tsushima rather projects the image of being the Japanese version of Namhae. Rural and, what the tourism brochures might describe as 'contemplative'. Perhaps Tsushima isn't like that, but if not, the official Korean tour did little to sell it. The tour itinerary included – and I'm not making this up – a primary school and two banks, in addition to two very small temples. At least the latter is more fitting with a trip to another country, I'm not so sure what a 'cultural visit' to a bank really gives the tourist.

Then there's the Japanese hotel experience. It had no toilet paper or anything else which couldn't be screwed down (to be fair I've stayed in a Japanese hotel and it wasn't like this – but then I wasn't on Tsushima). And the meals were apparently minimalistic – even by the minimalist standards of the Japanese. Hunger became the Koreans' constant travelling companion. It made me wonder whether, given the festering animosity the Korean territorial claims have created on Tsushima, these two facts were entirely disconnected.

So when Korean Mother got back, the first place she and her friends visited was a Korean restaurant near the ferry terminal. The manager saw the terrible hunger writ large across their faces and said “You've just come back from Daemado haven't you?”

Oh, and that plot thickening I promised? While they were being shown around Tsushima the Korean tour guide told the assembled visitors... “Daemado was Korean territory you know, but now Japan claims it is theirs, so we have to get it back...”

However... in March 2005 the local council in Korean city of Masan designated June 19 as Daemado Day, claiming that this was the date in 1419 the island was annexed by the Korean Joseon Dynasty. Therefore, Daemado is Korean territory. But this isn't necessarily just some Tea Party-style fringe movement; in 2008 50 members of the Korean parliament stated their support for the territorial claim over Tsushima, and an opinion poll at the time showed 50.6% support amongst Koreans for the claim. Read on for a little more plot thickening.

So Korean Mother went to Tsushima – or Daemado - and it was meant as a short holiday, not the advanced recon party for a future invasion. Apparently Korean trips to Tsushima are quite popular. I once read that back in the 1980s the best slogan the Korean tourist authorities could come up with for a Japanese campaign was the rather weak but technically correct “Korea – the closest country to Japan” - which is practically apologetic in its lacking of ideas regarding what was attractive about Korea at the time. Now the roles are reversed, because – to paraphrase - Tsushima is the closest part of Japan to Korea.

Unfortunately Tsushima rather projects the image of being the Japanese version of Namhae. Rural and, what the tourism brochures might describe as 'contemplative'. Perhaps Tsushima isn't like that, but if not, the official Korean tour did little to sell it. The tour itinerary included – and I'm not making this up – a primary school and two banks, in addition to two very small temples. At least the latter is more fitting with a trip to another country, I'm not so sure what a 'cultural visit' to a bank really gives the tourist.

Then there's the Japanese hotel experience. It had no toilet paper or anything else which couldn't be screwed down (to be fair I've stayed in a Japanese hotel and it wasn't like this – but then I wasn't on Tsushima). And the meals were apparently minimalistic – even by the minimalist standards of the Japanese. Hunger became the Koreans' constant travelling companion. It made me wonder whether, given the festering animosity the Korean territorial claims have created on Tsushima, these two facts were entirely disconnected.

So when Korean Mother got back, the first place she and her friends visited was a Korean restaurant near the ferry terminal. The manager saw the terrible hunger writ large across their faces and said “You've just come back from Daemado haven't you?”

Oh, and that plot thickening I promised? While they were being shown around Tsushima the Korean tour guide told the assembled visitors... “Daemado was Korean territory you know, but now Japan claims it is theirs, so we have to get it back...”

Tags:

culture,

foreigners,

government,

history,

pride,

tourism

Location:

Tsushima, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan

Thursday, November 04, 2010

The Hornet's Nest

Apparently Namhae has killer bees. Or something like that.

Korean Father was out very early in the morning on top of an isolated mountain mowing the grass around his mother's grave, during the last days of the summer's heat. It has to be done otherwise it would become unkempt and that would be disrespectful, and since graveyards in Korea are generally small and don't employ anyone to maintain them, it's a family responsibility. The graves of those with no nearby or surviving relatives can often easily be spotted as isolated patches of chaos in an otherwise ordered scene.

This particular morning Korean Father was stung three times by large hornets. It seems that this is OK as long as they don't get you in the head. Then you die. Really. In fact I understand that earlier this year a forty-two year old farmer died in Namhae after this happened to him, and there have been other deaths and incidents. The fourth sting caught Korean Father right between the eyes. His right eye began to lose focus, his lips numbed, he started to lose movement in his jaw, and his arms and legs weakened. He called a friend who's the head of a health clinic, and he phoned for an ambulance, which had to negotiate its way to the top of the mountain Korean Father had walked up. Fortunately there is a road, of sorts, although it's one of those Korean ones you really don't want to look down over the side of.

Fortunately with rapid treatment Korean Father quickly recovered, unlike some other unfortunate victims, although his face was still swollen days later.

Before city dwellers lull themselves into a false sense of security, according to the JoongAng Daily the Busan Fire Department had to administer first aid to 145 people this year, so clearly it's not an issue just confined to the countryside. And while we have a lot of bees and wasps (hornets) where I'm from, they pale in comparison to the Asian Giant Hornet, which grows up to two inches (50mm) in length, and injects a venom so strong it can dissolve human tissue.

So it seems like this is an important safety tip, beware of Korea's killer hornets...

Korean Father was out very early in the morning on top of an isolated mountain mowing the grass around his mother's grave, during the last days of the summer's heat. It has to be done otherwise it would become unkempt and that would be disrespectful, and since graveyards in Korea are generally small and don't employ anyone to maintain them, it's a family responsibility. The graves of those with no nearby or surviving relatives can often easily be spotted as isolated patches of chaos in an otherwise ordered scene.

This particular morning Korean Father was stung three times by large hornets. It seems that this is OK as long as they don't get you in the head. Then you die. Really. In fact I understand that earlier this year a forty-two year old farmer died in Namhae after this happened to him, and there have been other deaths and incidents. The fourth sting caught Korean Father right between the eyes. His right eye began to lose focus, his lips numbed, he started to lose movement in his jaw, and his arms and legs weakened. He called a friend who's the head of a health clinic, and he phoned for an ambulance, which had to negotiate its way to the top of the mountain Korean Father had walked up. Fortunately there is a road, of sorts, although it's one of those Korean ones you really don't want to look down over the side of.

Fortunately with rapid treatment Korean Father quickly recovered, unlike some other unfortunate victims, although his face was still swollen days later.

Before city dwellers lull themselves into a false sense of security, according to the JoongAng Daily the Busan Fire Department had to administer first aid to 145 people this year, so clearly it's not an issue just confined to the countryside. And while we have a lot of bees and wasps (hornets) where I'm from, they pale in comparison to the Asian Giant Hornet, which grows up to two inches (50mm) in length, and injects a venom so strong it can dissolve human tissue.

So it seems like this is an important safety tip, beware of Korea's killer hornets...

Location:

Busan, South Korea

Sunday, October 31, 2010

Radio Active

"One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of seeing things.” – Henry Miller

About once every two months I'm approached to write for a magazine, do a radio show or appear on TV, just because of this blog. Why? I'm not really sure. It's probably a similar story for the other foreign bloggers in Korea. Sometimes it seems people here desperately want to know what we think about Korea – although the vox populi vox dei (semper insaniae proxima) is the sword that potentially hangs over us if what we have to say veers too far off-script.

So while apparently these media offers are always a great opportunity for me to reach a wider audience, usually nobody seems to stop to consider whether this is really a good idea. Except me, so in the past I've always politely declined, for this and other reasons. In any case, I consider myself to have a face for radio and a voice for writing. In other words, I don't want to see myself on TV and I don't want to hear myself speaking. What's more, to some previous disappointment in Korea, sadly I don't have one of those Hugh Grant-style English accents – I'm from Northern England, where the accent – like so many other things – is a lot rougher. Writing a blog is about my level.

The latest invitation came from Busan e-FM, an English-language radio station here in the city, and it coincided with a few things including a bout of serious boredom I get every few years – or maybe it's a creeping sense of despair. Something needs to change – some new perspective needs to be added, no matter how small. So I decided to go over to the KNN building in Yeonsan-dong to talk to them about being a guest on one of their shows. It wasn't the first invite I'd had from the station – had my schedule allowed I would have accepted a different invitation several weeks earlier, but it didn't. I guess this means I've been bored for months.

By this time it had transpired that I was being invited in as a regular guest – once a week – to talk about my experiences living in Busan. And it follows – and I made sure – that not all my experiences can be positive ones so there would be certain topics that were more about the difficulties I'd faced. But that said, I've come to realise something important about living here in Korea. There isn't that much I really hate about it. I'd been avoiding the Korean media in part because of all my pent up 'Ignoreland'-style anger, except when I really sat down to think about it, I was mostly angry about other things and my quality of life in Korea was better than that of my life in England. So I believed I could talk on the radio and be genuinely 'fair and balanced' (in the true sense of the phrase – not the Fox News version) without upsetting anyone. Well, probably anyway. If there's one thing I don't like about Korea, it's that vox populi issue. People don't always need an excuse – or logic in the case of Tablo – to believe counter-factual dogma or to get angry about something, as I well know.

Before I even went on the air for the first time on Wednesday in the 'Open Mike in Busan' segment of the 'Inside Out Busan' show, I had already pushed my boundaries. The truth is - there's no getting away from it - it's a long time since I lived in the minor media spotlight, delivering speeches to audiences of hundreds and doing regular media spots. Ménière's Disease has left me a shadow of my former self, so whereas once a ten-minute weekly radio slot would barely have registered on my radar, now it's my own personal Everest. I've written this blog over the years to challenge myself into leading the most normal life possible; the desire to write about some event or place pushes me to go out and have that experience - but if it has portrayed the impression of normality it has been a façade. Now I've come to believe I'm in remission - or at least - the best remission I'm going to have, and I'm pushing the envelope of a tantalising possibility - that I might be able to lead a more normal life again, one in which I can work to a deadline, and make commitments to people that I can keep.

I'd also gained another new perspective. It was my first experience of working with Korean people professionally, and it's certainly been an education well worthy of detailed analysis in this blog. But there's a good rule with writing blogs, the machinations of your professional life stay private. Or to put it another way, the first rule of what happens in Busan e-FM, is that you do not talk about what happens in Busan e-FM. The second rule is that you DO NOT talk about what happens in Busan e-FM, and the third rule is that if someone yells “stop!”, goes limp or taps out, then it's over. So I'll have to save it for my memoirs.

But suffice to say, language and culture barriers can be difficult enough to overcome in social life, but when those barriers extend to business life, where important things are being done to a schedule, they can take on a whole new edge. And they certainly have – in fact I'm reminded of an old project management adage:

"I know that you believe that you understand what you think I said, but I am not sure you realise that what you heard is not what I meant.”

As always, the real problem is me. In this case, my lack of understanding of Korean business culture and my lack of understanding the Korean language. So perhaps this out of character decision of mine to stick my head above the parapet has already served a purpose. I have widened my perspective, seen the world from a different point of view, and realised – I have to up my game. For three years in Korea I have sat at my desk through some of the most turbulent times in financial history, and it has sucked away huge amounts of my time at the expense of the development of my Korean life. The longer this continues the more problems I will have here, so it can't. Whether I can do anything about it is a more open question – I feel like my IQ is dropping by about two points every year – which doesn't sound like much but it's a problem if I didn't have much to spare to begin with, and it mounts up. Learning Japanese fourteen years ago was much easier than this, and I didn't even live there.

In some respects it's a measure of how insulated my life here has been that I never listened to Busan e-FM until recently. Which is a great pity. Much of the Western foreigner experience in Korea centres around Seoul, in fact most of Korea seems to centre around Seoul. Korea reminds me a lot of those nesting Russian matryoshka dolls – if you live in Namhae you want to move to Busan, if you live in Busan you want to move to Haeundae, if you live in Haeundae you want to move to Seoul, and if you live in Seoul you want to move to Gangnam. What do people in Gangnam aspire to? Making even more money and 'enhancing their prestige' would be my guess. Anyway, I doubt they're really as happy as they might have us believe.

So even though Busan is the second city, for me it hasn't always felt as though there was a strong ex-pat community here – most Western foreigners seem to be in Seoul. Or at least, I never heard much from the Busan ex-pat community aside from the few discussions on the Busan-friendly Koreabridge. But these days some of that insight – that connection – is perhaps only ever a radio dial away, on Busan e-FM.

In fact it's a measure of my isolation that I will add what might be an interesting insight. Since coming here in 2006 I've spoken to one foreigner face-to-face, on one occasion, for about twenty minutes – he came into Gimbab Nara where I was eating. That was in 2007, and it's the kind of life you can lead embedded in a Korean family in the unfashionable Western edge of the city of Busan. On Wednesday evening, at Busan e-FM, I massively increased the number of foreigners I've ever met here in Busan from one to three. One of them is Tim, the new host of Inside Out Busan, who was great and really put my nerves at ease. Well, as much as possible in the edgy, nervous world I inhabit these days.

My time on Busan e-FM will be short, but I expect to be listening to Inside Out Busan long afterwards. For anyone with an interest who is unlucky enough to be living outside Busan, the podcasts or “AOD” (Audio-On-Demand) downloads can be found here. I'm afraid it seems to be Windows only, or at least ironically, it doesn't work on my Ubuntu system. Well, that's life in Korea for you.

About once every two months I'm approached to write for a magazine, do a radio show or appear on TV, just because of this blog. Why? I'm not really sure. It's probably a similar story for the other foreign bloggers in Korea. Sometimes it seems people here desperately want to know what we think about Korea – although the vox populi vox dei (semper insaniae proxima) is the sword that potentially hangs over us if what we have to say veers too far off-script.

So while apparently these media offers are always a great opportunity for me to reach a wider audience, usually nobody seems to stop to consider whether this is really a good idea. Except me, so in the past I've always politely declined, for this and other reasons. In any case, I consider myself to have a face for radio and a voice for writing. In other words, I don't want to see myself on TV and I don't want to hear myself speaking. What's more, to some previous disappointment in Korea, sadly I don't have one of those Hugh Grant-style English accents – I'm from Northern England, where the accent – like so many other things – is a lot rougher. Writing a blog is about my level.

The latest invitation came from Busan e-FM, an English-language radio station here in the city, and it coincided with a few things including a bout of serious boredom I get every few years – or maybe it's a creeping sense of despair. Something needs to change – some new perspective needs to be added, no matter how small. So I decided to go over to the KNN building in Yeonsan-dong to talk to them about being a guest on one of their shows. It wasn't the first invite I'd had from the station – had my schedule allowed I would have accepted a different invitation several weeks earlier, but it didn't. I guess this means I've been bored for months.

By this time it had transpired that I was being invited in as a regular guest – once a week – to talk about my experiences living in Busan. And it follows – and I made sure – that not all my experiences can be positive ones so there would be certain topics that were more about the difficulties I'd faced. But that said, I've come to realise something important about living here in Korea. There isn't that much I really hate about it. I'd been avoiding the Korean media in part because of all my pent up 'Ignoreland'-style anger, except when I really sat down to think about it, I was mostly angry about other things and my quality of life in Korea was better than that of my life in England. So I believed I could talk on the radio and be genuinely 'fair and balanced' (in the true sense of the phrase – not the Fox News version) without upsetting anyone. Well, probably anyway. If there's one thing I don't like about Korea, it's that vox populi issue. People don't always need an excuse – or logic in the case of Tablo – to believe counter-factual dogma or to get angry about something, as I well know.

Before I even went on the air for the first time on Wednesday in the 'Open Mike in Busan' segment of the 'Inside Out Busan' show, I had already pushed my boundaries. The truth is - there's no getting away from it - it's a long time since I lived in the minor media spotlight, delivering speeches to audiences of hundreds and doing regular media spots. Ménière's Disease has left me a shadow of my former self, so whereas once a ten-minute weekly radio slot would barely have registered on my radar, now it's my own personal Everest. I've written this blog over the years to challenge myself into leading the most normal life possible; the desire to write about some event or place pushes me to go out and have that experience - but if it has portrayed the impression of normality it has been a façade. Now I've come to believe I'm in remission - or at least - the best remission I'm going to have, and I'm pushing the envelope of a tantalising possibility - that I might be able to lead a more normal life again, one in which I can work to a deadline, and make commitments to people that I can keep.

I'd also gained another new perspective. It was my first experience of working with Korean people professionally, and it's certainly been an education well worthy of detailed analysis in this blog. But there's a good rule with writing blogs, the machinations of your professional life stay private. Or to put it another way, the first rule of what happens in Busan e-FM, is that you do not talk about what happens in Busan e-FM. The second rule is that you DO NOT talk about what happens in Busan e-FM, and the third rule is that if someone yells “stop!”, goes limp or taps out, then it's over. So I'll have to save it for my memoirs.

But suffice to say, language and culture barriers can be difficult enough to overcome in social life, but when those barriers extend to business life, where important things are being done to a schedule, they can take on a whole new edge. And they certainly have – in fact I'm reminded of an old project management adage:

"I know that you believe that you understand what you think I said, but I am not sure you realise that what you heard is not what I meant.”

As always, the real problem is me. In this case, my lack of understanding of Korean business culture and my lack of understanding the Korean language. So perhaps this out of character decision of mine to stick my head above the parapet has already served a purpose. I have widened my perspective, seen the world from a different point of view, and realised – I have to up my game. For three years in Korea I have sat at my desk through some of the most turbulent times in financial history, and it has sucked away huge amounts of my time at the expense of the development of my Korean life. The longer this continues the more problems I will have here, so it can't. Whether I can do anything about it is a more open question – I feel like my IQ is dropping by about two points every year – which doesn't sound like much but it's a problem if I didn't have much to spare to begin with, and it mounts up. Learning Japanese fourteen years ago was much easier than this, and I didn't even live there.

In some respects it's a measure of how insulated my life here has been that I never listened to Busan e-FM until recently. Which is a great pity. Much of the Western foreigner experience in Korea centres around Seoul, in fact most of Korea seems to centre around Seoul. Korea reminds me a lot of those nesting Russian matryoshka dolls – if you live in Namhae you want to move to Busan, if you live in Busan you want to move to Haeundae, if you live in Haeundae you want to move to Seoul, and if you live in Seoul you want to move to Gangnam. What do people in Gangnam aspire to? Making even more money and 'enhancing their prestige' would be my guess. Anyway, I doubt they're really as happy as they might have us believe.

So even though Busan is the second city, for me it hasn't always felt as though there was a strong ex-pat community here – most Western foreigners seem to be in Seoul. Or at least, I never heard much from the Busan ex-pat community aside from the few discussions on the Busan-friendly Koreabridge. But these days some of that insight – that connection – is perhaps only ever a radio dial away, on Busan e-FM.

In fact it's a measure of my isolation that I will add what might be an interesting insight. Since coming here in 2006 I've spoken to one foreigner face-to-face, on one occasion, for about twenty minutes – he came into Gimbab Nara where I was eating. That was in 2007, and it's the kind of life you can lead embedded in a Korean family in the unfashionable Western edge of the city of Busan. On Wednesday evening, at Busan e-FM, I massively increased the number of foreigners I've ever met here in Busan from one to three. One of them is Tim, the new host of Inside Out Busan, who was great and really put my nerves at ease. Well, as much as possible in the edgy, nervous world I inhabit these days.

My time on Busan e-FM will be short, but I expect to be listening to Inside Out Busan long afterwards. For anyone with an interest who is unlucky enough to be living outside Busan, the podcasts or “AOD” (Audio-On-Demand) downloads can be found here. I'm afraid it seems to be Windows only, or at least ironically, it doesn't work on my Ubuntu system. Well, that's life in Korea for you.

Tags:

Busan eFM,

business,

culture,

foreigners

Sunday, October 24, 2010

When the Smoke Clears

I really don't like mosquitoes, the dreaded Korean 'mogi'. Recently I related some of my mogi-chasing stories to someone here and she seemed to think it was more amusing than I did. When I got home, I asked my wife, "what's so funny about that?" She told me that Korean people don't usually bother enough about mosquitoes to spend an hour out of bed in the middle of the night chasing one with a newspaper. OK, that's fair enough, I may be a little crazy. But look at it this way - I'm a completer-finisher*. (*I wish - I'm actually a dangerously high scoring 'shaper').

But am I crazy enough to want to run trucks around crowded streets spraying insecticide at everyone? No - so who are the crazy ones now?

I didn't see this the first time I was here, but this summer one day I noticed a cloud of smoke in the distance. My first thought - that some old Hyundai Accent had finally reached its expiry point - proved incorrect.

It was, I was told, mosquito spraying. I'd heard about this, but thought it was a practice largely consigned to the past. Apparently not, it seemed, as the scene was repeated every couple of weeks thereafter.

It didn't look very healthy either, as the truck in our area dashed around the narrow streets spewing a chemical cloud behind it leaving people nowhere to hide.

Obviously, the insecticide is designed to kill mosquitoes rather than people, but I can't help thinking that it can't be particularly healthy, even if it won't kill you. And will this chemical concoction still be seen as safe in future? There was a time when people thought DDT was fine too.

But what I didn't expect, was to see one of these chemical spraying trucks do a circuit of the local school ground every two weeks, enveloping the children practising football in thick clouds of insecticide.

But perhaps this means if the Korean national team ever have to play a game in fog, they're bound to win.

Maybe it doesn't cause any lasting damage though. My wife used to run through the smoke chasing the trucks down the street because she said it was fun. That was when she was a child by the way, not recently - which would be more disturbing.

Now I'm a parent though, I watch that mosquito truck making its regular rounds of the local school, and think one day that could be my child enveloped in a chemical soup. I'm not really thrilled at the idea.

But does it work? Well, this summer was amazing for three months - I didn't see a single mosquito. But just as I was contemplating the notion that actually, it really does work, I read that the unusual weather this year meant that mosquito numbers were down significantly. However, as the autumn arrived they emerged with a vengeance. The mogi-trucks are still doing their rounds, I suppose they would argue that it would be worse if they didn't. But how can we know?

But am I crazy enough to want to run trucks around crowded streets spraying insecticide at everyone? No - so who are the crazy ones now?

I didn't see this the first time I was here, but this summer one day I noticed a cloud of smoke in the distance. My first thought - that some old Hyundai Accent had finally reached its expiry point - proved incorrect.

It was, I was told, mosquito spraying. I'd heard about this, but thought it was a practice largely consigned to the past. Apparently not, it seemed, as the scene was repeated every couple of weeks thereafter.

It didn't look very healthy either, as the truck in our area dashed around the narrow streets spewing a chemical cloud behind it leaving people nowhere to hide.

Obviously, the insecticide is designed to kill mosquitoes rather than people, but I can't help thinking that it can't be particularly healthy, even if it won't kill you. And will this chemical concoction still be seen as safe in future? There was a time when people thought DDT was fine too.

But what I didn't expect, was to see one of these chemical spraying trucks do a circuit of the local school ground every two weeks, enveloping the children practising football in thick clouds of insecticide.

But perhaps this means if the Korean national team ever have to play a game in fog, they're bound to win.

Maybe it doesn't cause any lasting damage though. My wife used to run through the smoke chasing the trucks down the street because she said it was fun. That was when she was a child by the way, not recently - which would be more disturbing.

Now I'm a parent though, I watch that mosquito truck making its regular rounds of the local school, and think one day that could be my child enveloped in a chemical soup. I'm not really thrilled at the idea.

But does it work? Well, this summer was amazing for three months - I didn't see a single mosquito. But just as I was contemplating the notion that actually, it really does work, I read that the unusual weather this year meant that mosquito numbers were down significantly. However, as the autumn arrived they emerged with a vengeance. The mogi-trucks are still doing their rounds, I suppose they would argue that it would be worse if they didn't. But how can we know?

Tags:

culture shock,

health,

safety,

weather

Location:

Busan, South Korea

Friday, October 15, 2010

Horror Hospital

Recently I wrote about some of the problems my wife and I had experienced with the maternity hospital we were in, but things were going to turn out to be worse for other people in what seemed to me like a perfect storm of Korean cultural issues.

The first aspect of Korean culture which differs from my own country lies in the fundamental nature of the birth experience itself. In Korea, women can – within a period of around four weeks - choose when to give birth; they pick a date and then report to the hospital to be induced or – if this is their preferred option, to have a caesarian section to deliver the baby. Now add to this ability to schedule a birth to the Korean thanksgiving holiday of Chuseok, one of those extremely rare times of the year when family might not be out working 12-hours a day, apparently making it a good time to schedule said birth. Next add in the near total contempt some business owners demonstrate for their customers in Korea, nurtured through a pathological pursuit of profit that might even make a financial trader blush. Add a little of the legendary local construction quality on top, and mix all these things together to achieve predictable results.

So this is what happened. A large number of women checked themselves in to have their babies during the Chuseok holiday, and it was probably double what the hospital could cope with. Normally, the recovery area of the maternity hospital, the 'sanhujoriwon' (산후조리원), takes up three floors – over Chuseok, the hospital expanded it to six by commandeering other floors which were not designed for the purpose. Whereas my wife's room was solely for her with en-suite, a desk, a TV and double bed for the husband to sleep in, the Chuseok mothers ended up in shared rooms with four beds and little else. That makes it no better than a bad British experience, and possibly worse because the already seemingly understaffed Korean hospital had not employed extra personnel for the holiday rush. Crucially for the people here though, this was not what they are accustomed to expecting, and it certainly wasn't what they were sold in the brochure.

And it gets worse. I said the hospital hadn't employed any extra staff, but in fact they'd gone the other way. The cleaning staff had the week off. So you have these new mothers, packed into rooms kept at abnormally high temperatures because of the belief here that this is better for their 'shattered' bodies, there's a lot of sweating and a lot of clothes going in the hospital wash baskets. But now nobody is around to clean them, piles of smelly clothes are building up in the corridors, and mothers are running out of clean clothes to wear. You can imagine the situation with bedding, bearing in mind that many of these women have undergone operations or procedures and were still bleeding.

And then there was the woman in the room next to us. Like my wife, she had been lucky enough to have her baby just before Chuseok, so she had a room to herself as she was supposed to. But the bathroom had a drainage problem. It was fitted incorrectly with the drainage grate too high, so after showering water would just collect creating an indoor pool. The room isn't exactly new so presumably it's been like this since it was built two or three years ago. She complained to the Sanhujoriwon Director - he offered her a small tool to push the water uphill into the pipe. She'd just given birth and could hardly walk, but the Samhujoriwon Director apparently thought nothing of her bending over pushing water around the floor. She protested.

Was he embarrassed? Afraid? His response was “If you don't like it, I have plenty of other women who would gladly have your room.” And sadly he was probably right, because when you're packed into a small room with three other women with no facilities whatsoever, you'd certainly see a single room with an inch of standing water in the bathroom as an upgrade. This is not really a good excuse, and it reminds me of the time I found a long black hair baked into my pizza at an expensive restaurant in Busan, and when we complained, the manager looked at us incredulously and said “well, it's only one.” On the face of it, Korea often seems to have a positive customer service culture – but perhaps only because they want to sell you something – once the transactions is done, attitudes can rapidly change – not always, but often enough to make you feel like you're stepping into a minefield every time.

It must have been bad because the husbands got unionised and all went to see the Hospital Director to complain, and by this time you can probably guess how that went. 'If you don't like my hospital, pick another!' I understand that a private Internet forum for mothers in Busan is now buzzing with anger about it, so word of mouth may at least provide a little karmic retribution.

Given the appalling conditions in the lower decks it almost seems churlish to mention another area in which the experience fell below expectations, but I will for completeness. The 'samhujoriwon' experience is about recovery and education, with mothers attending various classes to help them transition from hospital to coping on their own with their babies. There were no classes during Chuseok which meant that of the ten days of activities promised, many women only got seven. It's understandable that this is just bad luck and while I would expect cleaning to continue during the holiday, educational classes are a bit much to ask for. But there certainly won't be any refunds for the women who were short changed in this and other ways during the holidays. By this time, I couldn't say I was surprised.

Can I name and shame the hospital here? Sadly, probably not. The way things seem to work here is that criticising companies in public can easily lead to lawsuits. And in a nutshell, this tells you a lot about reason why the Hospital Director all but laughed in the faces of his patients and their families.

The problems I detail above effected others far more than they effected my wife. We were lucky – if you can call it luck - to have our own room away from some of the horrors. But I asked my wife, in principle rather than with intention, what could we have done to formally complain about the hospital had we suffered like some others had suffered. I was curious. She really wasn't sure, because often it seems people really don't ask those kind of questions here. I had an idea that ultimately, hospitals had to be licensed, and medical companies that ask new mothers to crawl around the bathroom floors of understaffed hospitals in dirty clothes are probably not what the government have in mind when handing out those licenses. So one imagines there must be some mechanism for calling people who run institutions like this to account. But it's not really my problem and it's a given that the Koreans who suffered won't take action either. Nothing will change. Meanwhile the Korean Government will keep talking about their desire to promote medical tourism to Korea within the Asian region, with discounts for properly qualified plumbers, presumably.

The first aspect of Korean culture which differs from my own country lies in the fundamental nature of the birth experience itself. In Korea, women can – within a period of around four weeks - choose when to give birth; they pick a date and then report to the hospital to be induced or – if this is their preferred option, to have a caesarian section to deliver the baby. Now add to this ability to schedule a birth to the Korean thanksgiving holiday of Chuseok, one of those extremely rare times of the year when family might not be out working 12-hours a day, apparently making it a good time to schedule said birth. Next add in the near total contempt some business owners demonstrate for their customers in Korea, nurtured through a pathological pursuit of profit that might even make a financial trader blush. Add a little of the legendary local construction quality on top, and mix all these things together to achieve predictable results.

So this is what happened. A large number of women checked themselves in to have their babies during the Chuseok holiday, and it was probably double what the hospital could cope with. Normally, the recovery area of the maternity hospital, the 'sanhujoriwon' (산후조리원), takes up three floors – over Chuseok, the hospital expanded it to six by commandeering other floors which were not designed for the purpose. Whereas my wife's room was solely for her with en-suite, a desk, a TV and double bed for the husband to sleep in, the Chuseok mothers ended up in shared rooms with four beds and little else. That makes it no better than a bad British experience, and possibly worse because the already seemingly understaffed Korean hospital had not employed extra personnel for the holiday rush. Crucially for the people here though, this was not what they are accustomed to expecting, and it certainly wasn't what they were sold in the brochure.

And it gets worse. I said the hospital hadn't employed any extra staff, but in fact they'd gone the other way. The cleaning staff had the week off. So you have these new mothers, packed into rooms kept at abnormally high temperatures because of the belief here that this is better for their 'shattered' bodies, there's a lot of sweating and a lot of clothes going in the hospital wash baskets. But now nobody is around to clean them, piles of smelly clothes are building up in the corridors, and mothers are running out of clean clothes to wear. You can imagine the situation with bedding, bearing in mind that many of these women have undergone operations or procedures and were still bleeding.

And then there was the woman in the room next to us. Like my wife, she had been lucky enough to have her baby just before Chuseok, so she had a room to herself as she was supposed to. But the bathroom had a drainage problem. It was fitted incorrectly with the drainage grate too high, so after showering water would just collect creating an indoor pool. The room isn't exactly new so presumably it's been like this since it was built two or three years ago. She complained to the Sanhujoriwon Director - he offered her a small tool to push the water uphill into the pipe. She'd just given birth and could hardly walk, but the Samhujoriwon Director apparently thought nothing of her bending over pushing water around the floor. She protested.