After a few minutes, I began to think that the number of car horns sounding outside, far below on the highway, was unusually high. A few minutes after that, I finally decided to get up from my desk and see what all the commotion was about. I expected there had been a breakdown or accident, instead I saw what I believed to be a cat, meandering around the six lanes as though it hadn't a care in the world. Cars were doing emergency stops, weaving around it at the last minute, and stopping dead as the animal chose to remain in front of their halted vehicles. Horns were being sounded, to no avail.

People were standing at the side of the road, but nobody was doing anything. One driver opened his car door, perhaps in the hope that the animal would jump in, but it didn't and they had to move off. Two minutes passed by and I just couldn't believe the scene unfolding before me. The cat had to be hit, it was simply a question of when. Once or twice it approached the side of the road, but inexplicably each time walked back towards the centre. I watched a car swerve in avoidance at the last moment, straight into the path of a truck which somehow missed it. The animal was going to be killed, and there was every chance there was going to be a serious accident. I'd asked my wife to phone the police but it didn't seem to be happening, and in any case I knew what had to be done, even if I didn't particularly like cats.

Descending fifteen floors in an elevator seems an excruciatingly long journey when you're trying to go to an animal's rescue. I waited with Korean Mother who'd run out to join me - more I think to keep me out of trouble than in some consideration for the cat outside. When the doors finally opened, all I could say in English before I sprinted off was "you'll have to catch me up", in the hope that somehow she'd understand the sentiment. Assessing the situation from ground level was much harder than from my grandstand view above, but within half a minute I'd spotted the animal, which transpired to be a dog, not a cat. Now I was even more determined.

The dog was moving at a walking pace down the road as I ran to catch it up. Finally it moved across the road just enough to bring the three lanes of traffic at my side to a momentary halt. I'd seen this scene play out from above - the drivers would be speeding off again within a couple of seconds, so I had to seize my chance. I ran out into the middle of the road where two yellow lines separated me and the dog from the traffic speeding by us in the opposite lanes. I knew the dog could be vicious - even rabid - so despite getting this far, now I needed to try and grab the animal in as non-threatening a way as possible while trying to watch out for vehicles potentially bearing down on us both. I grew up with dogs but the crazy animal we rescued two years ago became the first dog that ever bit me, drawing blood - an act he has since repeated randomly several times. I was very cautious.

I moved my arms as slowly towards the dog as I could risk given the time pressure, but he snapped at me. We were dangerously close to being on the side of the road where the traffic wasn't stopped, and I knew that any sudden movements might cause the dog to suddenly jump away from me into the path of an oncoming car. My path of retreat was threatened as one of the cars behind me started moving forward, and I felt I had to withdraw. The dog would have to come off the road on its own. No doubt the onlookers wondered why I didn't just grab it considering I already risking my life, but once bitten, twice shy. And they wouldn't have my wife to deal with afterwards either if I returned to the apartment with teeth marks in my hand.

The other problem with being out in the middle of the road, contrary to law, is that if anything bad happened, I suspected I was going to get the blame for it, and being a foreigner might just make the ramifications worse. Voltaire wrote that "Common sense is not so common", but my time in Korea has led me to the alarming realisation that common sense is merely a cultural perspective. As an Englishman, common sense told me to do something wrong to prevent a greater tragedy. The inaction of the Koreans suggests it was common sense to them to stay off the road and not get involved. Who's to say they aren't right?

I indicated to Korean Mother, who had caught up with me by this time, that the dog might be vicious and she should call the police - '경찰. 전화.' - 'Police. Phone.' It was the best I could do. I didn't think the police would care about the dog, but they should at least care about the danger of a serious accident occurring on the road. I offered her my phone, which I'd had the presence of mind to grab on my way out. But it wasn't getting through. 'Police. Phone. Police. Phone.' Finally she replied - '일 - 일 - 구. 일 - 일 - 구.' It took a moment for me to absorb the unexpected direction this conversation was going in. 'One - One - Nine. One - One - Nine.' The number for the police. Sensing my confusion she signed the numbers with her fingers. I must have given her a complete look of despair - I know the number for the police, the problem is talking to them, "I can't speak Korean" I told her in Korean. The penny dropped "Ohhh!" she replied.. This was still, however, frustratingly not getting the police call made, so as I ran to catch up with the dog I called my wife back at the apartment and asked her to make it instead, while I attempted a new strategy of coaxing the dog to the side of the road with nothing but an anxious look. At any moment I knew I was going to see the dog run over at high speed in front of me. It promised to be awful. A car finally hit him at low speed, which was fortunately only enough to knock him off balance momentarily before he resumed his course.

The dog doubled back on itself and began to drift onto the opposite side of the road, so I ran to the other side using the subway underpass, but by the time I emerged the dog had finally left the road and ventured into a narrow street on the side I'd just left. Korean Mother was gesturing to me - I had to run back while phoning my wife to tell her to cancel the police - she was already worried that they might view her call to be a prank and fine her. "There are a hundred witnesses out here" I told her, and while I'd been largely oblivious to the crowd, there probably were. But this at least provided a possible explanation as to the continued reluctance by all concerned to involve the police and the odd absence of any law enforcement presence some fifteen minutes into the start of this chaos on a major road.

I found the dog around the back of a building in a narrow passageway that was blocked at the end. It was finally trapped, but appeared much friendlier now it was off the road. My plan was to slowly gain its trust. Korean Mother's plan was evidently to walk down the passageway and force the issue. A little over two years ago she was nervous around dogs as many people here are prone to being in my experience, now she was befriending an unfamiliar and traumatised animal out on the street. She rapidly won him over.

We took him to the nearby vets where the lone assistant finally agreed to keep him temporarily. It was a logical place for an owner to look for their lost dog, and we couldn't have taken him back to our apartment anyway - partly because of the aggressive dog we already have there and partly because my wife's pregnancy demands that no strange animals are suddenly introduced to the environment.

It seemed that after two days if no-one came forward he would be sent on to another organisation that would 'deal with him'. He might get rehoused, and he might not, with the latter outcome probably being a death sentence. I was determined not to allow the latter and had already found the Korean Animal Protection Society and Animal Rescue Korea when a call to the vets before they closed revealed that the dog had already been reunited with its owner.

And that's how I very probably risked my life yesterday doing something apparently no sane Korean person would do - which is running out into the middle of a busy six-lane highway trying to rescue an animal while a frozen audience looked on. What people must have thought of me running up and down the road, into it, trying to coax the dog to safety I can't be sure, but some of that frozen audience who were still milling around and who talked to Korean Mother afterwards told her they thought it must be my dog. So perhaps the Korean version of this story is 'crazy foreigner carelessly lets his dog stray into the road'.

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

Monday, April 26, 2010

Quarantine

When I spend time with our Korean friends, we share experiences, but not often thoughts or conversation; they can't speak much English and I can't speak much Korean. When they laugh, I don't get the joke, when they suddenly decide to do something, I usually don't vote, only follow. The language barrier separates us and it's easy to fall into an isolation of my own thoughts and my own world. It's a frustrating reminder that the time I've spent studying has not yielded adequate results, and while I try to follow what those around me are saying, it requires a sustained level of concentration which my mind seems ill-equipped for after all the hundreds of ups and downs of fifty-five hour trading week. It was with some trepidation then, that I opted to extend the experience from a few hours to an entire weekend spent at the summer house of one of our group, two hours north of Busan in Hapcheon County ('합천군'), West of Daegu.

Recently Korea has suffered from an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease, and once we left the highway one of the realities of this became evident as our stuffed minivan was quickly subjected to decontaminating spray at a checkpoint. It wasn't the last; shortly before we reached the isolated valley in the mountains that was our destination, we had to repeat the experience. It may only be a matter of time before movement is prevented entirely as it had to be in the UK in 2001.

When we drove down the final mountain the valley that emerged before us comprised of six or seven small dwellings clustered amongst the fields. It was the type of place which was so small and dispersed you had to wonder whether it could even be called a village. I'd expected our weekend home to be a rather ramshackle building in keeping with the vast majority of Korean rural architecture and my experiences in Namhae, but the rather smart metal gates we pulled up at suggested otherwise, and these were opened to reveal an entirely modern single-story house beyond, which in turn opened up to reveal a modest but functional three room dwelling comprising of a bedroom, kitchen/living area, and a bathroom.

Our friend, the owner, has a full-time job in Busan. I'd been told he grew vegetables here, but the variety of crops visible, along with the size of the plot of land - which even included a pond - made it evident that this was no mere side operation but a serious commitment. It seemed he was leading a double life as a farmer at the weekends.

Namhae hadn't prepared me for this. The nearest road was a thin strip visible in the far distance, and even then it wasn't well traversed. In-between the bird song it wasn't just quiet, there was an actual absence of noise. I couldn't remember the last time I'd experienced anything like it. It was breathtaking - and perhaps because Meniere's Disease has left me with mild Hyperacusis, enormously relieving. People always seem surprised when they read of traders who give up their lives in the city to become farmers - moving from the frenetic pace of the city to the perceived tranquillity of a job which seems right at the other end of the career spectrum as far as one's environment is concerned. While I'd always sympathised with the sentiment, at that moment I understand it perfectly.

After a barbecue, to which every fly in Hapcheon County had been invited, the plan was for the group to go 'night fishing'. It had been warm in the sun but as we'd eaten and dusk had fallen, the temperature had become surprisingly cold, promising to turn the experience not so much into a battle against the fish, as a battle against the elements. But once again language and cultural barriers highlighted the difference between my English understanding of the act of going out 'fishing' and the Korean definition. We drove out to a river near an isolated love hotel, getting sprayed for foot-and-mouth disease again on our way in and out, where nets were prepared on a low concrete bridge in very little light. Once prepared, the nets were tied to the bridge supports. And that was it - no rods, no braving the near freezing conditions, no waiting around in vain for hours - just drop your nets in and leave. Two hours later the nets were collected - two fish had been caught.

We were all up the next morning at 7am because we'd come here with a purpose of sorts - to help dig foundations for a new outbuilding and harvest some of the vegetables. An early mist hung in the valley but it wasn't long before a surprisingly strong sun burnt it off. I also got burnt - I'd spent an hour clearing stones from the fields to be used around the pond, and while I put on sun-cream when I went in for breakfast, the damage had already been done.

At 9am my image of the idyllic rural scene was somewhat shattered by the sound of a disembodied voice echoing around the valley. I realised later there were speakers on some of the telegraph poles, and the authorities weren't afraid to use them. A foot-and-mouth warning was read out. It repeated every couple of hours, and at one point a car broadcasting a similar message even made its way down the valley. Now that I've worked out in the fields while loudspeakers broadcast government warnings I feel I've had a little taste of the North Korean experience. On the whole, it seems strange that such a potential invasion of privacy would be put up with, no matter what the 'public good' arguments are, but given that our apartment back in Busan has a similar loudspeaker which 'important' messages are broadcast through - with no way of turning it off - perhaps people here are conditioned to be used to disembodied voices of authority speaking to them in their private moments.

I suppose it's not as though they are used to urge people to work harder in the fields - not that it would perhaps be needed - who needs Big Brother when you have your dead ancestors watching over you in the fields from their graves in the hills?

We completed collecting stones from the land and the 'Oriental Fire-Bellied Toads' ('Bombina orientalis') now had a more interesting environment to live in. The toads, as their name suggests, have rather spectacular orange undersides to warn of their toxicity, but they weren't easy subjects to photograph.

The foundations began to take shape, but digging was hard work as the ground was full of stones and rocks. The building was being referred to as a summer house, which appeared to make it a summer house for the summer house. There seemed to be a Russian doll thing going on here. From the haphazard nature of our work, I harboured a suspicion that in Korea, if you wake up one morning and decide to build a new building on your land you just go ahead and do it - there's little if anything in the way of planning permission to resolve. Or at least, there didn't seem to be anything other than an ad-hoc plan.

Later I helped harvest some vegetables before lunch, and in the afternoon sawed some wood - my wife wanted to make a traditional wooden object which is meant to usher in good harvests - it's basically a wooden base with a small vertical branch connected to horizontal, vertical and then horizontal branch, all progressively smaller. The alleged effect is that of a bird perched on a branch.

We'd been on a tight schedule all weekend, in fact there was an actual schedule printed out in some detail, and our time was almost at an end. We left our brief rural life and returned to the city, where the 'Meowi'/'머위' vegetables (or Meogu/머구 as they are called in the Busan dialect) were a big hit with Korean Mother. Apparently they are really hard to find or buy in Busan because not many people eat it here, even though many people like Korean Mother are ultimately immigrants from more rural places. I'm told it tasted especially delicious. When I closed my eyes, I could still see dozens of black dots flying around. I can only imagine this place is mosquito hell in summer.

During the trip I seriously began to wonder how I was perceived by my Korean friends. My wife, who normally acts as my translator, was elsewhere most of the time, and unlike at social gatherings I found myself in situations where I needed to coordinate with others or follow instructions, but it was hard to do. I felt that if I were a Korean, I'd probably be regarded as having a rather low IQ, but then this is the reality of my Korean existence so perhaps for the purposes of defining my Korean life, I am thus mentally challenged. At one point I was asked if I knew how to use a spade. I don't know how it is that the deeper I get into Korean life the more isolated I feel, and can only hope this is an inverse Bell-Curve of which I will one day find myself on the opposite, ascending side. I never expected my experiences to get worse as time went on, and that's the surprise and disappointment.

I tried to work very hard to compensate, but I was sorry that between this and the tight schedule I never had the chance to leave the compound and walk around the area. Life in rural Korea is radically different to life in the cities, and I thought there must be much to discover. I also really needed that elusive perfect moment of tranquillity that was hinted at, and the faintest promise of some enlightenment it might carry with it, but instead it seemed we exported our city lives into the countryside, changed one form of work for another, and kept the same urban pace that is so much a part of our existence.

Recently Korea has suffered from an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease, and once we left the highway one of the realities of this became evident as our stuffed minivan was quickly subjected to decontaminating spray at a checkpoint. It wasn't the last; shortly before we reached the isolated valley in the mountains that was our destination, we had to repeat the experience. It may only be a matter of time before movement is prevented entirely as it had to be in the UK in 2001.

When we drove down the final mountain the valley that emerged before us comprised of six or seven small dwellings clustered amongst the fields. It was the type of place which was so small and dispersed you had to wonder whether it could even be called a village. I'd expected our weekend home to be a rather ramshackle building in keeping with the vast majority of Korean rural architecture and my experiences in Namhae, but the rather smart metal gates we pulled up at suggested otherwise, and these were opened to reveal an entirely modern single-story house beyond, which in turn opened up to reveal a modest but functional three room dwelling comprising of a bedroom, kitchen/living area, and a bathroom.

Our friend, the owner, has a full-time job in Busan. I'd been told he grew vegetables here, but the variety of crops visible, along with the size of the plot of land - which even included a pond - made it evident that this was no mere side operation but a serious commitment. It seemed he was leading a double life as a farmer at the weekends.

Namhae hadn't prepared me for this. The nearest road was a thin strip visible in the far distance, and even then it wasn't well traversed. In-between the bird song it wasn't just quiet, there was an actual absence of noise. I couldn't remember the last time I'd experienced anything like it. It was breathtaking - and perhaps because Meniere's Disease has left me with mild Hyperacusis, enormously relieving. People always seem surprised when they read of traders who give up their lives in the city to become farmers - moving from the frenetic pace of the city to the perceived tranquillity of a job which seems right at the other end of the career spectrum as far as one's environment is concerned. While I'd always sympathised with the sentiment, at that moment I understand it perfectly.

After a barbecue, to which every fly in Hapcheon County had been invited, the plan was for the group to go 'night fishing'. It had been warm in the sun but as we'd eaten and dusk had fallen, the temperature had become surprisingly cold, promising to turn the experience not so much into a battle against the fish, as a battle against the elements. But once again language and cultural barriers highlighted the difference between my English understanding of the act of going out 'fishing' and the Korean definition. We drove out to a river near an isolated love hotel, getting sprayed for foot-and-mouth disease again on our way in and out, where nets were prepared on a low concrete bridge in very little light. Once prepared, the nets were tied to the bridge supports. And that was it - no rods, no braving the near freezing conditions, no waiting around in vain for hours - just drop your nets in and leave. Two hours later the nets were collected - two fish had been caught.

We were all up the next morning at 7am because we'd come here with a purpose of sorts - to help dig foundations for a new outbuilding and harvest some of the vegetables. An early mist hung in the valley but it wasn't long before a surprisingly strong sun burnt it off. I also got burnt - I'd spent an hour clearing stones from the fields to be used around the pond, and while I put on sun-cream when I went in for breakfast, the damage had already been done.

At 9am my image of the idyllic rural scene was somewhat shattered by the sound of a disembodied voice echoing around the valley. I realised later there were speakers on some of the telegraph poles, and the authorities weren't afraid to use them. A foot-and-mouth warning was read out. It repeated every couple of hours, and at one point a car broadcasting a similar message even made its way down the valley. Now that I've worked out in the fields while loudspeakers broadcast government warnings I feel I've had a little taste of the North Korean experience. On the whole, it seems strange that such a potential invasion of privacy would be put up with, no matter what the 'public good' arguments are, but given that our apartment back in Busan has a similar loudspeaker which 'important' messages are broadcast through - with no way of turning it off - perhaps people here are conditioned to be used to disembodied voices of authority speaking to them in their private moments.

I suppose it's not as though they are used to urge people to work harder in the fields - not that it would perhaps be needed - who needs Big Brother when you have your dead ancestors watching over you in the fields from their graves in the hills?

We completed collecting stones from the land and the 'Oriental Fire-Bellied Toads' ('Bombina orientalis') now had a more interesting environment to live in. The toads, as their name suggests, have rather spectacular orange undersides to warn of their toxicity, but they weren't easy subjects to photograph.

The foundations began to take shape, but digging was hard work as the ground was full of stones and rocks. The building was being referred to as a summer house, which appeared to make it a summer house for the summer house. There seemed to be a Russian doll thing going on here. From the haphazard nature of our work, I harboured a suspicion that in Korea, if you wake up one morning and decide to build a new building on your land you just go ahead and do it - there's little if anything in the way of planning permission to resolve. Or at least, there didn't seem to be anything other than an ad-hoc plan.

Later I helped harvest some vegetables before lunch, and in the afternoon sawed some wood - my wife wanted to make a traditional wooden object which is meant to usher in good harvests - it's basically a wooden base with a small vertical branch connected to horizontal, vertical and then horizontal branch, all progressively smaller. The alleged effect is that of a bird perched on a branch.

We'd been on a tight schedule all weekend, in fact there was an actual schedule printed out in some detail, and our time was almost at an end. We left our brief rural life and returned to the city, where the 'Meowi'/'머위' vegetables (or Meogu/머구 as they are called in the Busan dialect) were a big hit with Korean Mother. Apparently they are really hard to find or buy in Busan because not many people eat it here, even though many people like Korean Mother are ultimately immigrants from more rural places. I'm told it tasted especially delicious. When I closed my eyes, I could still see dozens of black dots flying around. I can only imagine this place is mosquito hell in summer.

During the trip I seriously began to wonder how I was perceived by my Korean friends. My wife, who normally acts as my translator, was elsewhere most of the time, and unlike at social gatherings I found myself in situations where I needed to coordinate with others or follow instructions, but it was hard to do. I felt that if I were a Korean, I'd probably be regarded as having a rather low IQ, but then this is the reality of my Korean existence so perhaps for the purposes of defining my Korean life, I am thus mentally challenged. At one point I was asked if I knew how to use a spade. I don't know how it is that the deeper I get into Korean life the more isolated I feel, and can only hope this is an inverse Bell-Curve of which I will one day find myself on the opposite, ascending side. I never expected my experiences to get worse as time went on, and that's the surprise and disappointment.

I tried to work very hard to compensate, but I was sorry that between this and the tight schedule I never had the chance to leave the compound and walk around the area. Life in rural Korea is radically different to life in the cities, and I thought there must be much to discover. I also really needed that elusive perfect moment of tranquillity that was hinted at, and the faintest promise of some enlightenment it might carry with it, but instead it seemed we exported our city lives into the countryside, changed one form of work for another, and kept the same urban pace that is so much a part of our existence.

Tags:

culture,

food,

government,

language,

weather

Monday, April 19, 2010

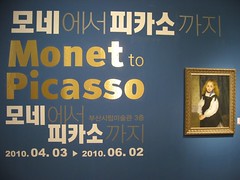

Surviving Picasso

"Art is a lie that makes us realise the truth." - Pablo Picasso

The Philadelphia Museum of Art has an exhibition on tour in Korea entitled "Monet to Picasso". Having spent three months at the Seoul Arts Center, where it attracted over 100,000 visitors in little over a month, it's recently arrived at the Busan Museum of Modern Art in Haeundae-gu for a two-month stay. As the title suggests, the exhibition features famous masterpieces from artists such as Monet and Picasso, in addition to Cézanne, Degas, Gauguin, Manet, Matisse, Renoir and van Gogh. According to the Museum the insurance cost for the exhibition was around 1,000bn won (£586m/$894m), which I suppose puts the collected value into some sort of perspective.

Given that Haeundae-gu is on the other side of Busan from us, it took an hour to get their by subway. It would have been forty-five minutes by bus, but if you have to stand that means a forty-five minute physical workout as the driver alternates between emergency braking and acceleration. Haeundae is an interesting part of Busan which has a number of places of cultural interest in close proximity - the Busan Exhibition and Convention Center for example - better known as BEXCO, is just across the road from the Museum. Unfortunately Haeundae isn't in any way centrally located, being out at the very edge of the subway network, so it isn't very convenient for many. On the other hand, given that Haeundae is the Dubai of Busan, perhaps the museums and exhibition centres are in the right place.

The ticket price was 12,000 won (around £7/$11) per person. Audio guides could be rented for 3,000 won, which read an explanation for 33 of the 96 masterpieces, providing a total running time of 50 minutes. This would have been quite useful, given that beyond the name of the artist, the year of their birth and death, the name of the work and the year it was created, there was no attempt to explain anything specifically about the piece, but unfortunately it was only available in Korean. That's a shame because one can imagine the exhibition attracting tourists with an interest in art from nearby countries such as Japan and China, not to mention the English-speaking expatriate community within Korea.

It's also possible to go on a guided tour of selected artwork within the exhibition, but I wouldn't recommend it. While we moved around the Museum a herd of around 40 people stomped their way around in a hot and chaotic pursuit of their guide, who had to talk from a platform with a microphone. It was clear that views of the paintings were hopelessly obscured.

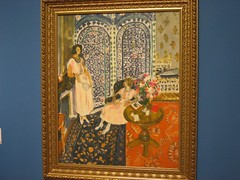

The exhibition itself was arranged into four galleries each with a separate theme - respectively Realism and Modern Life, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Picasso and the Avante-Garde, and American Art. Each at least had an opening explanation in Korean and English for those without audio guides. Most works were paintings, but amongst the famous sculptures were Constantin Brâncuşi's The Kiss (1916), Rodin's Eternal Springtime, and Picasso's Owl.

The exhibition itself was arranged into four galleries each with a separate theme - respectively Realism and Modern Life, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Picasso and the Avante-Garde, and American Art. Each at least had an opening explanation in Korean and English for those without audio guides. Most works were paintings, but amongst the famous sculptures were Constantin Brâncuşi's The Kiss (1916), Rodin's Eternal Springtime, and Picasso's Owl.

Photos aren't allowed within the exhibit of course, although a couple of copies of the genuine paintings visitors have just seen hang on the walls of the 'photo zone'.

Beyond this, the Chosun Ilbo currently has an reasonable overview in English and Korean, and the Philadephia Museum of Art's website carries information on such representative works as van Gogh's Still Life with a Bouquet of Daises, Manet's U.S.S. "Kearsarge" and the C.S.S. "Alabama", Renoir's Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, Degas' Ballet Class and Matisse's Yellow Odalisque.

The nature of the audio guide meant that my wife stopped at particular paintings for much longer than others, so rather than browse each one equally I was left waiting at certain pieces and then passing over others more quickly than I might otherwise had done. Unfortunately the friends we'd arrived with were making their own pace too, so we didn't want to be holding them up at the end.

After the main exhibit, we went to investigate a couple of side galleries containing the work of Vietnamese artists, and had just entered another containing a Japanese collection when a member of staff politely told us they would be closing in a few minutes. We'd entered the Museum at the admittedly late time of 3.30pm, but apparently it was now 7pm. Somehow, the time had flown by. It was a pity because there was clearly a lot more to investigate in the Museum, and while the genuine art enthusiast must consider coming face to face with an original work by the likes of Monet or Picasso as something of a pilgrimage, I was equally happy looking at the paintings of Kim Chong Hak, so perhaps a return trip is on the horizon.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art has an exhibition on tour in Korea entitled "Monet to Picasso". Having spent three months at the Seoul Arts Center, where it attracted over 100,000 visitors in little over a month, it's recently arrived at the Busan Museum of Modern Art in Haeundae-gu for a two-month stay. As the title suggests, the exhibition features famous masterpieces from artists such as Monet and Picasso, in addition to Cézanne, Degas, Gauguin, Manet, Matisse, Renoir and van Gogh. According to the Museum the insurance cost for the exhibition was around 1,000bn won (£586m/$894m), which I suppose puts the collected value into some sort of perspective.

Given that Haeundae-gu is on the other side of Busan from us, it took an hour to get their by subway. It would have been forty-five minutes by bus, but if you have to stand that means a forty-five minute physical workout as the driver alternates between emergency braking and acceleration. Haeundae is an interesting part of Busan which has a number of places of cultural interest in close proximity - the Busan Exhibition and Convention Center for example - better known as BEXCO, is just across the road from the Museum. Unfortunately Haeundae isn't in any way centrally located, being out at the very edge of the subway network, so it isn't very convenient for many. On the other hand, given that Haeundae is the Dubai of Busan, perhaps the museums and exhibition centres are in the right place.

The ticket price was 12,000 won (around £7/$11) per person. Audio guides could be rented for 3,000 won, which read an explanation for 33 of the 96 masterpieces, providing a total running time of 50 minutes. This would have been quite useful, given that beyond the name of the artist, the year of their birth and death, the name of the work and the year it was created, there was no attempt to explain anything specifically about the piece, but unfortunately it was only available in Korean. That's a shame because one can imagine the exhibition attracting tourists with an interest in art from nearby countries such as Japan and China, not to mention the English-speaking expatriate community within Korea.

It's also possible to go on a guided tour of selected artwork within the exhibition, but I wouldn't recommend it. While we moved around the Museum a herd of around 40 people stomped their way around in a hot and chaotic pursuit of their guide, who had to talk from a platform with a microphone. It was clear that views of the paintings were hopelessly obscured.

The exhibition itself was arranged into four galleries each with a separate theme - respectively Realism and Modern Life, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Picasso and the Avante-Garde, and American Art. Each at least had an opening explanation in Korean and English for those without audio guides. Most works were paintings, but amongst the famous sculptures were Constantin Brâncuşi's The Kiss (1916), Rodin's Eternal Springtime, and Picasso's Owl.

The exhibition itself was arranged into four galleries each with a separate theme - respectively Realism and Modern Life, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Picasso and the Avante-Garde, and American Art. Each at least had an opening explanation in Korean and English for those without audio guides. Most works were paintings, but amongst the famous sculptures were Constantin Brâncuşi's The Kiss (1916), Rodin's Eternal Springtime, and Picasso's Owl.Photos aren't allowed within the exhibit of course, although a couple of copies of the genuine paintings visitors have just seen hang on the walls of the 'photo zone'.

Beyond this, the Chosun Ilbo currently has an reasonable overview in English and Korean, and the Philadephia Museum of Art's website carries information on such representative works as van Gogh's Still Life with a Bouquet of Daises, Manet's U.S.S. "Kearsarge" and the C.S.S. "Alabama", Renoir's Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, Degas' Ballet Class and Matisse's Yellow Odalisque.

The nature of the audio guide meant that my wife stopped at particular paintings for much longer than others, so rather than browse each one equally I was left waiting at certain pieces and then passing over others more quickly than I might otherwise had done. Unfortunately the friends we'd arrived with were making their own pace too, so we didn't want to be holding them up at the end.

After the main exhibit, we went to investigate a couple of side galleries containing the work of Vietnamese artists, and had just entered another containing a Japanese collection when a member of staff politely told us they would be closing in a few minutes. We'd entered the Museum at the admittedly late time of 3.30pm, but apparently it was now 7pm. Somehow, the time had flown by. It was a pity because there was clearly a lot more to investigate in the Museum, and while the genuine art enthusiast must consider coming face to face with an original work by the likes of Monet or Picasso as something of a pilgrimage, I was equally happy looking at the paintings of Kim Chong Hak, so perhaps a return trip is on the horizon.

Monday, April 12, 2010

The Lost Words

In June 1950 the North Korean Army crossed the 38th parallel, invading the Republic of South Korea. By September, most of the Republic had fallen, with only the area around the city of Busan, or Pusan as it was then known in English, remaining under the control of anti-Communist forces. As the Republic collapsed, half a million refugees fled south to the coastal city, swelling the population to around 1.4 million. The Battle of Pusan Perimeter raged, and conditions within the titular city were equally chaotic.

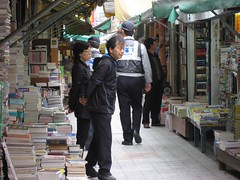

The Bosudong area of Busan became home to a significant number of refugees who had fled the Nothern advance. One displaced couple began selling old magazines from the U.S. military, and this quickly expanded in scope as the impoverished sold or pawned their books. Even as the war continued into 1951, seventy percent of children in Busan still attended primary school, even if classes were held in the open air. The proximity of many such 'provisional schools' in Bosudong ensured the growth of the second-hand book market, and the number of shops grew until by the 1960s there were around seventy crammed together in the narrow 'Bosudong Book Street' ('보수동 책방 골목'). The speed of the North Korean advance during the war had separated many families and friends, and the 'Book Street' also became a place for refugees to meet, socialise and perhaps search for those they had lost, long after hostilities had ended.

Today, sixty years after the war began, 'Bosudong Book Street' still exists and has become part of Busan's cultural heritage, and there is also, perhaps inevitably, an annual festival.

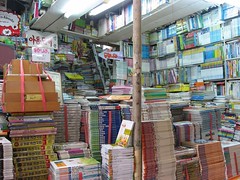

The street is not really a street at all for most of its length, but rather a narrow passageway with book shops of various shapes and sizes on both sides. In itself, this might create a rather disorganised feeling, but the effect is only heightened by the contents of the stores, many of which feature chaotic stacks of books placed everywhere there is a space. Often this spills out into the 'street' itself, only serving to make it even narrower. Along with the tarpaulins over the front of the shops to protect the books from the elements, it combines to create a somewhat claustrophobic atmosphere.

Inside the shops, the chaotic theme continues, with careful navigation a priority, and an acceptance that this may not be a place for the tall - even I had to duck under a large beam to reach one part of the upper floor of one particular store.

Most books were Korean, but not all of them. I was surprised to find one shop filled with old books in English, most of the titles and authors of which must surely have been long forgotten in the West. An ageing and probably unloved tribute to Western circa-1970s pulp fiction.

In addition to the decorative sewer grates which never detract from the emerging stench but are a regular feature of Busan's cultural districts, the street itself features tributes to the great works of literature such as Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne and Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky.

We'd planned on visiting 'Bosudong Book Street' for a number of weeks, but the night before the local news did a piece on an photo exhibition about the street that was being held until the weekend, so we expected that the publicity might result in the street being busy. In fact it wasn't busy at all, which was both surprising and a little saddening. It seems that in recent years, the character of the street has begun to change, as economic prosperity created more demand for new books. And while second-hand books can still be found in abundance, one suspects that the chaos of the second-hand book market is slowly giving way to a more ordered and modern consumer experience. As much as poverty created this place, wealth may be changing it fundamentally.

The black and white photos featuring the owners of the remaining Book Street stores looked out over an empty space at the Bosudong Catholic Exhibition Center.

The Bosudong area of Busan became home to a significant number of refugees who had fled the Nothern advance. One displaced couple began selling old magazines from the U.S. military, and this quickly expanded in scope as the impoverished sold or pawned their books. Even as the war continued into 1951, seventy percent of children in Busan still attended primary school, even if classes were held in the open air. The proximity of many such 'provisional schools' in Bosudong ensured the growth of the second-hand book market, and the number of shops grew until by the 1960s there were around seventy crammed together in the narrow 'Bosudong Book Street' ('보수동 책방 골목'). The speed of the North Korean advance during the war had separated many families and friends, and the 'Book Street' also became a place for refugees to meet, socialise and perhaps search for those they had lost, long after hostilities had ended.

Today, sixty years after the war began, 'Bosudong Book Street' still exists and has become part of Busan's cultural heritage, and there is also, perhaps inevitably, an annual festival.

The street is not really a street at all for most of its length, but rather a narrow passageway with book shops of various shapes and sizes on both sides. In itself, this might create a rather disorganised feeling, but the effect is only heightened by the contents of the stores, many of which feature chaotic stacks of books placed everywhere there is a space. Often this spills out into the 'street' itself, only serving to make it even narrower. Along with the tarpaulins over the front of the shops to protect the books from the elements, it combines to create a somewhat claustrophobic atmosphere.

Inside the shops, the chaotic theme continues, with careful navigation a priority, and an acceptance that this may not be a place for the tall - even I had to duck under a large beam to reach one part of the upper floor of one particular store.

Most books were Korean, but not all of them. I was surprised to find one shop filled with old books in English, most of the titles and authors of which must surely have been long forgotten in the West. An ageing and probably unloved tribute to Western circa-1970s pulp fiction.

In addition to the decorative sewer grates which never detract from the emerging stench but are a regular feature of Busan's cultural districts, the street itself features tributes to the great works of literature such as Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne and Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky.

We'd planned on visiting 'Bosudong Book Street' for a number of weeks, but the night before the local news did a piece on an photo exhibition about the street that was being held until the weekend, so we expected that the publicity might result in the street being busy. In fact it wasn't busy at all, which was both surprising and a little saddening. It seems that in recent years, the character of the street has begun to change, as economic prosperity created more demand for new books. And while second-hand books can still be found in abundance, one suspects that the chaos of the second-hand book market is slowly giving way to a more ordered and modern consumer experience. As much as poverty created this place, wealth may be changing it fundamentally.

The black and white photos featuring the owners of the remaining Book Street stores looked out over an empty space at the Bosudong Catholic Exhibition Center.

Friday, April 09, 2010

Mr. Bean

One of the great things about my wife's pregnancy is that she's been getting cravings for Western food, which normally she can happily live without. This prompted her to start searching for Heinz beans, or 'Beanz' as they prefer to call them these days for the benefit of Generation-Y.

Here, far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable end of the western spiral arm of Busan, I've only seen an actual can of baked beans once - it was allegedly the product of an Italian brand I'd never heard of, and it was too salty. So I didn't think my wife's quest specifically for Heinz beans was going to be successful, but she found some on the Internet. Considering that, as far as I recall, a pack of four tins of 'Heinz Beanz' in the UK used to sell for around £1.40 (2,402 won/$2.13), at 13,660 won for six (£8/$12) delivered, the Korean price was not cheap, although since they were not quite the classic product but instead 'ham sauce' and 'sweet chilli' flavour, it wasn't exactly comparing like with like. Clearly though, it was very expensive, but for the sake of the craving and that little reminder of home, we ordered them.

This being Korea, the beans turned up the next day, by which time my wife's few-day old craving had passed. The spiciness of the sweet chilli beans made wonder how they hadn't yet caught on in modern-day Korea, given that Koreans actually eat a lot of beans of the non-baked variety. Then again, the red beans which are so popular in Korea are believed to cast out bad spirits, but I don't believe Heinz Beanz have the same effect.

Later, friends of ours reported discovering the same product in the Busan branch of Costco, which unfortunately is too far away from us to shop at. The cost there is 9,990 won (£6/$9). They bought some for us and we gave them a tin of the sweet chilli beans guessing that these would be best suited to the spice-craving Korean palate. It proved to be a hit.

Here, far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable end of the western spiral arm of Busan, I've only seen an actual can of baked beans once - it was allegedly the product of an Italian brand I'd never heard of, and it was too salty. So I didn't think my wife's quest specifically for Heinz beans was going to be successful, but she found some on the Internet. Considering that, as far as I recall, a pack of four tins of 'Heinz Beanz' in the UK used to sell for around £1.40 (2,402 won/$2.13), at 13,660 won for six (£8/$12) delivered, the Korean price was not cheap, although since they were not quite the classic product but instead 'ham sauce' and 'sweet chilli' flavour, it wasn't exactly comparing like with like. Clearly though, it was very expensive, but for the sake of the craving and that little reminder of home, we ordered them.

This being Korea, the beans turned up the next day, by which time my wife's few-day old craving had passed. The spiciness of the sweet chilli beans made wonder how they hadn't yet caught on in modern-day Korea, given that Koreans actually eat a lot of beans of the non-baked variety. Then again, the red beans which are so popular in Korea are believed to cast out bad spirits, but I don't believe Heinz Beanz have the same effect.

Later, friends of ours reported discovering the same product in the Busan branch of Costco, which unfortunately is too far away from us to shop at. The cost there is 9,990 won (£6/$9). They bought some for us and we gave them a tin of the sweet chilli beans guessing that these would be best suited to the spice-craving Korean palate. It proved to be a hit.

Tuesday, April 06, 2010

The Republic

Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?

My wife and I are members of a newly formed social group in Busan. There are a lot of groups like this in Korea variously meeting up for cultural activities, going out and engaging in charitable activities. The new group plans to do all three.

In a culture where there are reckoned to be two million Internet addicts, inevitably there is an online forum for members, and I felt obliged to participate. Because the forum is run by Daum, one of the Korean Internet oligopolists, it isn't possible to just register by creating a user name and password as you might expect to with an equivalent Western web site. Instead, it's necessary to submit a full national ID number, or in the case of foreigners, the ID number from their 'Alien Registration Card', along with a full official name as per one's identity documents.

In other words if I'm to fully participate in Korean society, which these days is in no small part conducted online, I must forego my anonymity and potentially associate my name with every aspect of that life, with all the loss of privacy and potential for governmental profiling that this entails. Is the Korean Government spying on its citizens, and casting a worryingly wide net in doing so? Quite possibly.

After I entered my identity number and full name, I then needed to authenticate my online identity with the Government's 'identity bureau', either by mobile phone, by verified banking digital signature, or by entering my credit card details. My mobile phone is in my wife's name for simplicity, ruling out that option, my banking key turned out not to work with the Government's badly designed software even though it works with my bank, and I wasn't thrilled about handing my credit card details over because I don't really trust them with it. But, I had to go with the latter option. It really didn't seem worth it but I took the view that sooner or later I was going to have to let the Government's computers open a file on me so that the software can, in principle, start building up the evidence that I'm anything they later accuse me of.

The other problem with joining is that now I feel obliged to participate in online conversations - but even though the main method of communication tends towards Twitter-like brevity, even then trying to construct the Korean takes me a long time. Still, it all helps with the language study, and in the end it's probably an inevitable part of the process of integrating further into Korean society.

My wife and I are members of a newly formed social group in Busan. There are a lot of groups like this in Korea variously meeting up for cultural activities, going out and engaging in charitable activities. The new group plans to do all three.

In a culture where there are reckoned to be two million Internet addicts, inevitably there is an online forum for members, and I felt obliged to participate. Because the forum is run by Daum, one of the Korean Internet oligopolists, it isn't possible to just register by creating a user name and password as you might expect to with an equivalent Western web site. Instead, it's necessary to submit a full national ID number, or in the case of foreigners, the ID number from their 'Alien Registration Card', along with a full official name as per one's identity documents.

In other words if I'm to fully participate in Korean society, which these days is in no small part conducted online, I must forego my anonymity and potentially associate my name with every aspect of that life, with all the loss of privacy and potential for governmental profiling that this entails. Is the Korean Government spying on its citizens, and casting a worryingly wide net in doing so? Quite possibly.

After I entered my identity number and full name, I then needed to authenticate my online identity with the Government's 'identity bureau', either by mobile phone, by verified banking digital signature, or by entering my credit card details. My mobile phone is in my wife's name for simplicity, ruling out that option, my banking key turned out not to work with the Government's badly designed software even though it works with my bank, and I wasn't thrilled about handing my credit card details over because I don't really trust them with it. But, I had to go with the latter option. It really didn't seem worth it but I took the view that sooner or later I was going to have to let the Government's computers open a file on me so that the software can, in principle, start building up the evidence that I'm anything they later accuse me of.

The other problem with joining is that now I feel obliged to participate in online conversations - but even though the main method of communication tends towards Twitter-like brevity, even then trying to construct the Korean takes me a long time. Still, it all helps with the language study, and in the end it's probably an inevitable part of the process of integrating further into Korean society.

Tags:

culture,

foreigners,

government,

Internet,

language,

technology

Location:

Busan, South Korea

Friday, April 02, 2010

The Jazz Singer

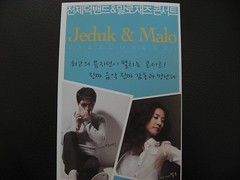

Three years ago we went to Pusan National University to see Jeon Jeduk (전제덕), a famous Korean harmonica player who was making an all-too-rare foray down to Korea's second city. He was back in town yesterday - for one day only - holding a concert with a woman regarded as one of this country's most famous jazz singers, who has been described as Korea's Ella Fitzgerald - perhaps in reference to her ability with scat singing. She's simply known as 'Malo' (말로). This time it was no mere university campus the concert would be held at, but rather Busan's Citizen's Hall in Beomildong.

I'd seen a clip of the two artistes performing together in a piece on our video-on-demand service, and while I knew what to expect with Jeon Jeduk, I was impressed with what I saw of Malo. But, I do like Jazz, and while I'm not sure about the Ella Fitzgerald reference, she certainly seemed to compare favourably with the likes of Diana Krall. Here's a video from Korean TV - featuring Malo and Jeduk performing Devil May Care with Malo's scat singing, followed by a less frenetic piece:

If you're not like me and you don't like rain then the weather was atrocious. By yesterday evening the downpour had turned into a deluge and while Jeon Jeduk thanked the audience for turning up in such conditions, even though his blindness meant that he couldn't have seen just how bedraggled we might have all looked.

To call it a joint concert between Jeduk and Malo would not really be correct, because the emphasis was more on the former than the latter. This imbalance was not what my wife felt had been advertised - I noticed that on the poster for the event at the venue it mentioned Jeduk with Malo in much smaller writing as a 'guest', but I gather that was the only place that this was actually stated. The flyer for example tends to imply a much more equal rating. Well, that's Korean advertising for you. A more difficult issue is what you define as jazz. The concert was advertised as a jazz concert and while my wife was happy enough that most of the content fell within definition I wasn't so sure. I may be old fashioned.

At least when Malo eventually took to the stage she was everything promised. A couple of songs were in English, which I had some mixed feelings about. I've heard the classics sung by native English speakers of most nationalities, but there's something about hearing them sung with a non-native accent which always feels ever-so-slightly off to me - I'd be remiss in relating the experience if I wasn't honest about it. I can easily lose myself in a truly mesmerising song but finding that moment of perfection can be harder when I'm hearing the pronunciation. I expect the longer I'm here the more I'll get used to it.

We ranged through Jazz music to Soul and Korean pop classics of the 1970s and 80s which were not jarring at all even if I'd have preferred to stay firmly fixed within the jazz genre. I wasn't really able to take any photos and videos until the encores when it became acceptable to do so.

The rarity of the trip to Busan had prompted one of the guitarists into something special - Jeon Jeduk had persuaded him to propose to his girlfriend - who was in the audience - on stage in the middle of the concert. However, this is not quite what you might think - they have arranged to get married in two weeks anyway, but such is the way things are done in Korea that he technically hasn't proposed yet. Well, it seems to me that it's a done deal now and far too late for her to say 'no' - Koreans don't have the same tradition of backing out of weddings as we do in the West (the loss of family face would be extraordinary) - but it was probably the most awkward proposal I've ever seen, with neither of them saying anything in the end and Jeon Jeduk gently chastising them for it afterwards.

The unscheduled diversion took the concert beyond its slated 90-minute running time and with the encore we were pushing 10pm when things finally came to a close, having started at 8pm. At 50,000 won per ticket (£29/$44) I'm not sure it was that cheap by Korean standards. To my mind it was worth it despite the minor disappointments, but then sometimes in Busan it feels like you have to take what you can get. Apparently, we're a long way from Seoul.

I'd seen a clip of the two artistes performing together in a piece on our video-on-demand service, and while I knew what to expect with Jeon Jeduk, I was impressed with what I saw of Malo. But, I do like Jazz, and while I'm not sure about the Ella Fitzgerald reference, she certainly seemed to compare favourably with the likes of Diana Krall. Here's a video from Korean TV - featuring Malo and Jeduk performing Devil May Care with Malo's scat singing, followed by a less frenetic piece:

If you're not like me and you don't like rain then the weather was atrocious. By yesterday evening the downpour had turned into a deluge and while Jeon Jeduk thanked the audience for turning up in such conditions, even though his blindness meant that he couldn't have seen just how bedraggled we might have all looked.

To call it a joint concert between Jeduk and Malo would not really be correct, because the emphasis was more on the former than the latter. This imbalance was not what my wife felt had been advertised - I noticed that on the poster for the event at the venue it mentioned Jeduk with Malo in much smaller writing as a 'guest', but I gather that was the only place that this was actually stated. The flyer for example tends to imply a much more equal rating. Well, that's Korean advertising for you. A more difficult issue is what you define as jazz. The concert was advertised as a jazz concert and while my wife was happy enough that most of the content fell within definition I wasn't so sure. I may be old fashioned.

At least when Malo eventually took to the stage she was everything promised. A couple of songs were in English, which I had some mixed feelings about. I've heard the classics sung by native English speakers of most nationalities, but there's something about hearing them sung with a non-native accent which always feels ever-so-slightly off to me - I'd be remiss in relating the experience if I wasn't honest about it. I can easily lose myself in a truly mesmerising song but finding that moment of perfection can be harder when I'm hearing the pronunciation. I expect the longer I'm here the more I'll get used to it.

We ranged through Jazz music to Soul and Korean pop classics of the 1970s and 80s which were not jarring at all even if I'd have preferred to stay firmly fixed within the jazz genre. I wasn't really able to take any photos and videos until the encores when it became acceptable to do so.

The rarity of the trip to Busan had prompted one of the guitarists into something special - Jeon Jeduk had persuaded him to propose to his girlfriend - who was in the audience - on stage in the middle of the concert. However, this is not quite what you might think - they have arranged to get married in two weeks anyway, but such is the way things are done in Korea that he technically hasn't proposed yet. Well, it seems to me that it's a done deal now and far too late for her to say 'no' - Koreans don't have the same tradition of backing out of weddings as we do in the West (the loss of family face would be extraordinary) - but it was probably the most awkward proposal I've ever seen, with neither of them saying anything in the end and Jeon Jeduk gently chastising them for it afterwards.

The unscheduled diversion took the concert beyond its slated 90-minute running time and with the encore we were pushing 10pm when things finally came to a close, having started at 8pm. At 50,000 won per ticket (£29/$44) I'm not sure it was that cheap by Korean standards. To my mind it was worth it despite the minor disappointments, but then sometimes in Busan it feels like you have to take what you can get. Apparently, we're a long way from Seoul.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)