Just over 400 years ago Japan invaded Korea in the first phase of a plan to conquer China, leading to a war on the Korean peninsula that lasted the best part of seven years before the Japanese, who had enjoyed initial successes, succumbed to their inability to maintain supply lines to their homeland as a result of Korea's massive naval technology superiority in the form of its turtle ships.

Just over 400 years ago Japan invaded Korea in the first phase of a plan to conquer China, leading to a war on the Korean peninsula that lasted the best part of seven years before the Japanese, who had enjoyed initial successes, succumbed to their inability to maintain supply lines to their homeland as a result of Korea's massive naval technology superiority in the form of its turtle ships.Samurai of the day were paid by the number of kills they made, or heads taken if you will, except that they didn't take the heads but rather cut off the noses of their enemies, and sometimes the ears. It seems that by the time the Japanese gave up, between 38,000 and 100,000 ears and noses had found their way back to Japan, where they were displayed, in pickled jars, in Osaka. That wasn't all that worked its way back to Japan; 200,000 Korean artisans had been kidnapped ultimately contributing much to the cultural renaissance under the Tokugawa Shogunate, while Korea was left devastated. Most of captured Koreans never returned home - it's said that as many as 100,000 were sold as slaves to the Portugese and sent to their colonies.

Eventually though, it was the body parts that remained a problem. They came to be buried in a mound in Kyoto called Mimizuka, and 400 years later Korea wants them back, or rather given their total decomposition in the intervening period, it wants Japan to give it the surrounding dirt instead...

Korean Father had a medical recently, and while there's not much of great concern, the doctor thinks it would be a good idea if he could stop winding himself up over just about everything. More Dalai Lama and less Beat Takeshi if you will. To this end, Korean Mother dragged him along to a talk on meditation held by a famous monk. Whatever discussions on higher spirituality went on, the subject turned to the war 400 years ago and specifically, the desire to repatriate the ears and noses, or rather the few tonnes of earth that now occupy the place where they were.

In 1990 the monk successfully negotiated with the Japanese government and brought back some "soil and spirits" but since then there's been no progress. The Kyoto burial mound is guarded so while Koreans go there to visit they can't hatch a plan to liberate it bit by bit. The monk wants to build a memorial to what happened - and preferably get that soil. And that's where the plate comes in.

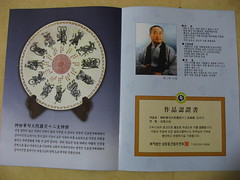

The monk has, it seems, been busy making plates - and bowls - as part of the effort, and these were available for the attendees to take away, free of charge. To pay for them the recipients should place their spare money in the bowl and when the amount reaches 39,900 won (about £21.73) it should be sent off to him. And there should be a total of ten payments of this amount, with the proceeds going towards the memorial. The monk personally painted the figures and writing on the plates as well as making and painting the bowls, and in that respect they have considerable artistic and aesthetic value, though their ultimate cost is not a logical one on a purely financial basis. It might seem very trusting of the monk to give these away, but people will pay of course. It's simply unthinkable not to hold up one end of a bargain with a monk, especially with as famous a one as this.

Aside from the cause, the plate depicts twelve Gods who will protect your family, and if you pray while picturing a particular person's face in the centre, they will be particularly protected. For reasons which are not entirely clear, the Gods are painted on a phosphorous coating the upshot of which is the plate glows eerily in the dark. And we have one sat by our TV now, because Korean Mother got one for herself, and one for us...